Hyponatremia Treatment Calculator

No calculation performed yet

When blood sodium falls below normal, Hyponatremia a condition characterized by serum sodium concentration under 135mmol/L can trigger a cascade of problems. Understanding whether the drop happened quickly or over weeks changes everything from symptoms to treatment, and that’s why the distinction between hyponatremia types matters.

What Is Hyponatremia?

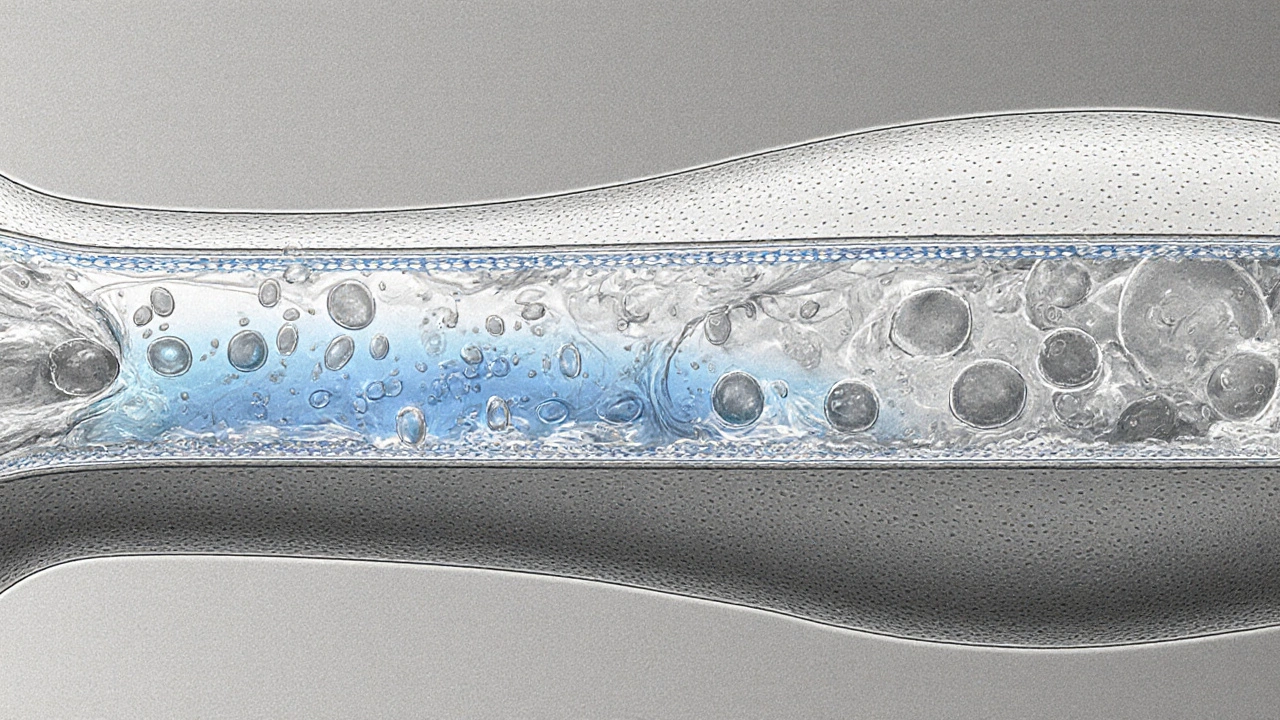

Sodium is the main extracellular ion; it helps regulate fluid balance, nerve impulse transmission, and muscle contraction. The body keeps serum sodium tightly within 135‑145mmol/L using hormones like antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and mechanisms in the kidneys. When excess water dilutes sodium, the resulting low concentration is called hyponatremia. Mild cases may be asymptomatic, but a rapid fall overwhelms the brain’s ability to adapt, leading to swelling and potentially life‑threatening neurological signs.

Acute Hyponatremia: Fast‑Acting Danger

Acute hyponatremia develops within 48hours and often presents with rapid neurological decline is usually tied to sudden water overload or a rapid loss of sodium. Common triggers include marathon running, intense endurance sports, binge drinking, and the administration of hypotonic IV fluids. Because the brain cannot expel water quickly enough, cerebral edema can cause headache, nausea, vomiting, seizures, and loss of consciousness.

Laboratory values often show serum sodium < 120mmol/L, and patients may present with altered mental status that fluctuates hour by hour. The urgency lies in preventing irreversible brain injury, so clinicians prioritize rapid but controlled correction.

Chronic Hyponatremia: A Slow‑Burn Issue

Chronic hyponatremia develops over days to weeks and allows the brain to adapt gradually often goes unnoticed. It is frequently seen in older adults with heart failure, cirrhosis, or chronic kidney disease, and in patients taking thiazide diuretics or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The gradual onset gives brain cells time to extrude osmolytes, reducing the risk of severe edema.

Serum sodium typically hovers between 125‑134mmol/L. Symptoms are subtle: mild fatigue, gait instability, mild confusion, or occasional falls. Because the condition is less dramatic, it can persist for months, increasing the risk of falls and fractures, especially in the elderly.

How Doctors Distinguish the Two

Accurate classification relies on timing, clinical context, and lab trends. A thorough history pinpoints rapid fluid intake (e.g., finishing a 5‑liter sports drink in a short period) versus chronic factors like diuretic use. Serial sodium measurements show whether the level is dropping fast or plateauing. Neuroimaging (CT or MRI) may reveal brain edema in acute cases but is often normal in chronic situations.

Additional labs help: serum osmolality, urine osmolality, and urine sodium differentiate between water‑excess states and sodium‑loss states. Elevated ADH levels-often measured indirectly via urine concentration-point toward conditions such as SIADH (Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion), a common cause of chronic hyponatremia.

Treatment Strategies: One Size Does Not Fit All

Because the brain’s adaptive state differs, treatment protocols vary dramatically.

- Acute hyponatremia: Goal is to raise serum sodium quickly enough to reduce cerebral edema, but not so fast that osmotic demyelination occurs. Hypertonic saline (3% NaCl) is the cornerstone, administered in boluses of 100mL over 10‑20minutes, repeated until symptoms improve. Frequent monitoring (every 15‑30minutes) guides further dosing. In some cases, vasopressin antagonists (vaptans) are added to block the effect of ADH.

- Chronic hyponatremia: The emphasis shifts to safe, gradual correction-no more than 8‑10mmol/L in 24hours. Fluid restriction (usually 800‑1000mL/day) is the first line. If restriction fails, oral salt tablets or loop diuretics can be used. For SIADH, demeclocycline or a vaptan may be prescribed. In severe chronic cases where sodium is < 120mmol/L but symptoms are mild, low‑dose hypertonic saline can be given under strict monitoring.

In both scenarios, addressing the underlying cause-whether stopping a hyponatremic medication or treating heart failure-prevents recurrence.

Prevention and Long‑Term Monitoring

Prevention starts with patient education. Athletes should avoid excessive water intake and replace electrolytes during prolonged exercise. Older adults on diuretics need regular sodium checks and counseling about fluid limits. For patients with known SIADH, clinicians often schedule monthly serum sodium tests and adjust medications promptly.

Home monitoring tools, like point‑of‑care electrolyte strips, are emerging but should complement, not replace, lab tests. Telehealth visits every 4‑6weeks for high‑risk patients improve adherence to fluid‑restriction plans and allow early detection of trend shifts.

Quick Reference Checklist

- Identify onset: Acute = <48hrs, Chronic = >48hrs.

- Check serum sodium: <120mmol/L (high‑risk acute), 125‑134mmol/L (common chronic).

- Assess symptoms: rapid neurological decline vs. subtle fatigue/falls.

- Start treatment: hypertonic saline for acute; fluid restriction for chronic.

- Monitor correction rate: ≤10mmol/L/24hrs (chronic), more aggressive but controlled for acute.

- Treat root cause: stop offending meds, manage heart/kidney disease, adjust ADH‑related disorders.

When to Seek Immediate Medical Help

If you experience sudden severe headache, confusion, seizures, or loss of consciousness-especially after intense exercise, excessive water intake, or IV fluid administration-call emergency services. Early intervention can prevent permanent brain damage.

| Aspect | Acute Hyponatremia | Chronic Hyponatremia |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Hours to 48hrs | Days to weeks |

| Typical Serum Na⁺ | <120mmol/L | 125‑134mmol/L |

| Common Causes | Water intoxication, rapid IV fluids, endurance sports | Heart failure, cirrhosis, SIADH, thiazides |

| Main Symptoms | Severe headache, nausea, seizures, altered mental status | Fatigue, gait instability, mild confusion, falls |

| First‑Line Treatment | 3% hypertonic saline bolus, possible vaptan | Fluid restriction, oral salt, treat underlying cause |

| Correction Speed | Rapid but monitored (≤12mmol/L/24hrs) | Slow (≤8‑10mmol/L/24hrs) |

Frequently Asked Questions

What sodium level defines hyponatremia?

Hyponatremia is diagnosed when serum sodium falls below 135mmol/L. Severity is graded as mild (130‑134), moderate (125‑129), and severe (<125).

Why can rapid correction cause damage?

If sodium rises too fast, brain cells shrink as they expel osmolytes, leading to osmotic demyelination syndrome, which can cause permanent neurological deficits.

Can a low‑salt diet trigger hyponatremia?

A low‑salt diet alone rarely causes hyponatremia unless combined with excessive water intake or an underlying disorder that impairs sodium retention.

Is SIADH always chronic?

SIADH typically presents as chronic hyponatremia because ADH secretion stays inappropriately high over days to weeks, allowing the brain to adapt slowly.

When should hypertonic saline be avoided?

In patients with chronic hyponatremia and no severe neurological symptoms, hypertonic saline is usually avoided to prevent over‑correction and demyelination.

Abby VanSickle

October 16, 2025 AT 16:27Thank you for the comprehensive overview. The distinction between acute and chronic hyponatremia is indeed critical for clinicians, as the therapeutic window differs markedly. Acute cases demand rapid intervention to mitigate cerebral edema, whereas chronic presentations require a cautious, incremental correction to avoid osmotic demyelination. Your inclusion of specific serum sodium thresholds and the recommended monitoring intervals provides clear guidance for emergency and ward settings alike. Moreover, the emphasis on underlying etiologies-such as SIADH and diuretic use-underscores the necessity of a holistic diagnostic approach. Overall, the article balances pathophysiological detail with practical treatment algorithms, which should aid both trainees and seasoned practitioners.

chris macdaddy

October 17, 2025 AT 10:33Yo this looks solid.

Moumita Bhaumik

October 18, 2025 AT 04:36Everyone needs to realize that the medical establishment is deliberately downplaying the risks of chronic hyponatremia to keep the pharmaceutical industry rolling out cheap diuretics and salt‑free diet pills. They hide the truth behind a flood of jargon, and only a few brave souls see through the smoke.

mike putty

October 18, 2025 AT 22:40Great summary! I appreciate how you highlighted the importance of patient education, especially for athletes and older adults. Small changes in fluid intake can make a huge difference in preventing these issues.

Kayla Reeves

October 19, 2025 AT 16:43While the article is factually correct, it glosses over the moral responsibility of doctors to prevent avoidable iatrogenic hyponatremia. Prescribing hypotonic IV fluids without strict monitoring is negligent, and the medical community should hold itself accountable.

Abhinanda Mallick

October 20, 2025 AT 10:46Patriotic physicians should prioritize our nation's health by demanding stricter regulations on imported diuretics that threaten our citizens. Only a decisive, elite approach can safeguard the blood sodium levels of hardworking Americans.

Richard Wieland

October 21, 2025 AT 04:50Acute hyponatremia is a race against time; chronic hyponatremia is a marathon of careful management.

Carys Jones

October 21, 2025 AT 22:53The piece fails to address the ethical implications of using vaptans for chronic cases, which are often prescribed off‑label and can be prohibitively expensive. Such oversight reflects a troubling complacency in our healthcare discourse.

Roxanne Porter

October 22, 2025 AT 16:56I appreciate your balanced view on treatment options. Collaborative protocols that combine fluid restriction with patient‑specific pharmacotherapy can improve outcomes while respecting individual circumstances.

Jonathan Mbulakey

October 23, 2025 AT 11:00Reflecting on the article, one sees that the brain’s adaptability mirrors the philosophical notion of resilience: gradual exposure fosters equilibrium, sudden shocks disrupt it.

Warren Neufeld

October 24, 2025 AT 05:03This is a clear and helpful guide. The simple language makes it easy for patients to understand their condition.

Deborah Escobedo

October 24, 2025 AT 23:06Thank you for breaking down a complex topic into actionable steps. Patients will benefit from the concise checklist and the emphasis on regular monitoring.

Dipankar Kumar Mitra

October 25, 2025 AT 17:10Honestly, the whole discussion about sodium levels feels like a metaphor for our modern lives-constantly diluted by endless distractions. We need to concentrate, like the brain does, on what truly matters, or we’ll all just implode.

Tracy Daniels

October 26, 2025 AT 10:13First, let me say how much I appreciate the thoroughness of this article 😊. The distinction between acute and chronic hyponatremia is often muddled in many textbooks, and you’ve cleared that up with precise definitions. I also love the way you broke down the pathophysiology-explaining how ADH, renal handling, and extracellular fluid shifts interact gives readers a solid foundation. The clinical presentation sections are spot‑on; describing the neurological signs of acute cases versus the subtle gait instability in chronic scenarios helps clinicians recognize red flags early. Your discussion on diagnostic work‑up, especially the role of urine osmolality and sodium, provides a practical algorithm that can be directly applied in the emergency department.

Regarding treatment, the emphasis on controlled correction rates is crucial. I’ve seen too many cases where rapid over‑correction led to osmotic demyelination, and your reminder of the 8‑10 mmol/L per 24 h ceiling for chronic cases is a lifesaver. The inclusion of hypertonic saline boluses for acute symptomatic patients, as well as the optional use of vaptans, offers a comprehensive toolkit.

One area that could be expanded is the long‑term monitoring strategy for patients with recurrent hyponatremia. Incorporating telehealth check‑ins and home electrolyte testing kits, as you mentioned, is forward‑thinking, but adding a suggested frequency for lab follow‑up (e.g., monthly for high‑risk patients) would make the guidance even more actionable.

Overall, this piece is an excellent resource for both trainees and seasoned clinicians. Thank you for the clear writing, the helpful tables, and the practical take‑aways. Keep up the great work! 🌟