Combination Drug Risk Assessment Tool

Assess Your Combination Drug Risk

This tool evaluates the risk/benefit ratio of fixed-dose combination medications based on your current health profile. Based on WHO guidelines and clinical evidence from the article.

Think about your medicine cabinet. How many pills do you swallow each day? For someone managing high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol, it’s not unusual to juggle five or six different tablets. Now imagine taking just one pill that does it all. That’s the promise of combination drugs-fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) that bundle two or more active ingredients into a single tablet or capsule. They’re everywhere now: for hypertension, tuberculosis, HIV, Parkinson’s, and even some cancers. But behind the convenience lies a real trade-off: fewer pills might mean better adherence, but it also means less control-and potentially more risk.

Why Combination Drugs Exist

Combination drugs aren’t new. Traditional medicine systems, like Traditional Chinese Medicine, have used multi-ingredient formulas for centuries. But modern FDCs took off in the 1970s with combinations like sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim for bacterial infections. The goal was simple: make treatment easier. When patients have to take multiple pills, they often forget, skip doses, or stop altogether. Studies show that switching to a single pill can boost adherence by up to 30%. That’s not just a convenience-it’s a lifesaver.The World Health Organization recognized this early. By 2005, their Essential Medicines List included 18 fixed-dose combinations out of 312 total formulations. These weren’t random mixes. They were carefully chosen: rifampicin and isoniazid for tuberculosis, levodopa and carbidopa for Parkinson’s, and low-dose blood pressure combos like amlodipine and perindopril. Each one met strict criteria-drugs with different mechanisms, matching half-lives, and no dangerous overlaps in side effects.

The Real Benefits: More Than Just Fewer Pills

The biggest win with combination drugs is improved outcomes in complex diseases. Take hypertension. High blood pressure rarely has one cause. It’s often tied to fluid retention, artery stiffness, and overactive nerves. A single drug can’t fix all that. But a combo pill with a diuretic, a calcium blocker, and an ACE inhibitor? That’s a three-pronged attack. Research published in 2022 confirmed these combos lower blood pressure faster and more reliably than single agents. Patients on FDCs are also more likely to reach their target numbers.In cancer, combination therapies are standard. Tumors evolve resistance. Hit them with one drug, and they adapt. Hit them with three at once-each targeting a different pathway-and the cancer has nowhere to hide. Same with HIV: antiretroviral FDCs like Truvada or Triumeq combine drugs that block viral replication at different stages. This multi-target approach is why HIV is now a manageable condition, not a death sentence.

Even in tuberculosis, where treatment lasts six months or longer, FDCs have dramatically improved cure rates. In low-resource settings, where patients might travel hours for a clinic, a single daily pill means fewer missed doses and fewer drug-resistant strains developing.

The Hidden Costs: When Convenience Becomes a Trap

But here’s the catch: once you take the combo pill, you’re locked in. If your kidney function drops and your doctor needs to reduce the dose of one drug, you can’t just lower that one component. You have to switch to separate pills-or stop the whole regimen. That’s a problem if one ingredient causes an allergic reaction, interacts with a new medication, or suddenly becomes unsafe for you.Take a common FDC for hypertension: lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide. If you develop a cough from the lisinopril (a known side effect), you can’t just stop the ACE inhibitor and keep the diuretic. You have to abandon the whole pill. That means restarting treatment from scratch, possibly with a different combo or multiple prescriptions. For older adults on six or seven medications, this kind of disruption can lead to confusion, hospital visits, or worse.

And then there’s the risk of irrational combinations. Not all FDCs are created equal. In countries like India, where pharmaceutical manufacturing is massive, regulators have had to ban over 300 combination drugs because they had no proven benefit. Some combined two antibiotics with no scientific reason-just to sell more pills. The World Health Organization warns this kind of misuse fuels antimicrobial resistance, one of the biggest global health threats today.

Regulation: A Patchwork System

In the U.S., the FDA treats combination drugs as unique products. They don’t just approve the ingredients-they test the whole thing. Does the tablet dissolve properly? Do the drugs stay stable together? Do they interact in a way that increases toxicity? The FDA requires full data on safety, absorption, and side effects-even if each drug has been used alone for decades.But in other places, oversight is weaker. In some emerging markets, FDCs are sold without clinical trials. They’re copied from older formulas, repackaged, and pushed to pharmacies with little oversight. The result? Patients get pills that don’t work-or worse, cause harm. The Indian drug regulator, CDSCO, has repeatedly pulled unsafe combinations off shelves. But enforcement is slow, and black-market versions often reappear.

There’s also a gray area with compounded medications. These aren’t FDCs. They’re custom-made by pharmacists-for example, a topical cream with gabapentin, ketamine, and baclofen for nerve pain. These aren’t FDA-approved. The agency doesn’t check them before they’re sold. They’re meant for rare cases where standard pills won’t work, like for patients who can’t swallow pills or are allergic to fillers. But some clinics push them as “miracle cures,” blurring the line between personalized care and unregulated risk.

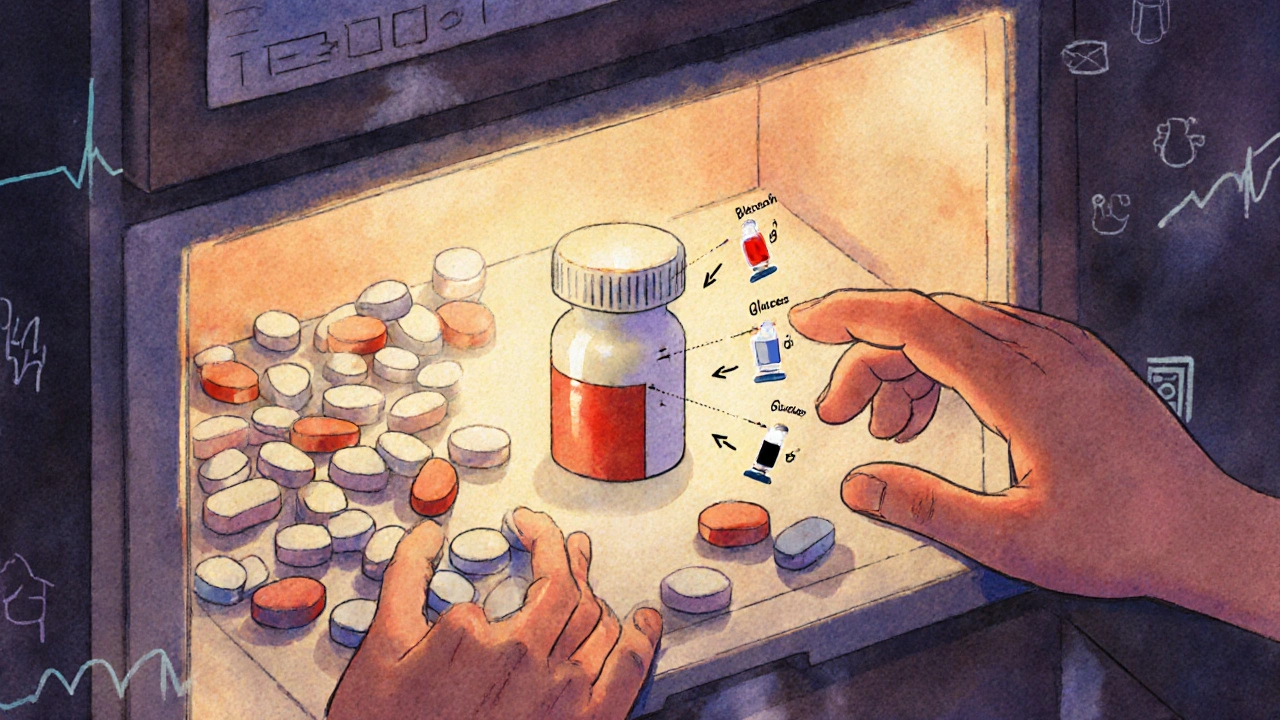

What Makes a Good Combination?

Not every mix is smart. A rational FDC must meet three basic rules:- Different mechanisms: The drugs should attack the disease in separate ways-like one lowering blood pressure by relaxing arteries, another by flushing out fluid.

- Matching timing: Both drugs should last about the same amount of time in your body. If one wears off in four hours and the other lasts 12, you’ll get uneven effects.

- No dangerous overlap: Don’t combine two drugs that both strain the liver or both cause dizziness. The risk multiplies.

That’s why some combos are approved and others aren’t. Levodopa and carbidopa work because carbidopa blocks the breakdown of levodopa in the bloodstream, letting more reach the brain. It’s a smart partnership. But a combo of two NSAIDs? That’s just doubling down on stomach bleeding risk with no added benefit.

What Patients Should Know

If you’re on a combination drug, ask these questions:- Why was this combo chosen over separate pills?

- What happens if I need to stop one ingredient?

- Are there any known interactions with other meds I take?

- Is this combination on the WHO Essential Medicines List?

Don’t assume it’s safer just because it’s one pill. And don’t be afraid to ask for alternatives. If you’re having side effects, your doctor might be able to switch you to a different combo-or even separate pills with a simpler schedule.

For chronic conditions, adherence is everything. But if the pill doesn’t fit your body, it doesn’t matter how convenient it is. The goal isn’t fewer pills-it’s the right treatment, safely delivered.

What’s Next?

The future of combination drugs isn’t about stuffing more ingredients into one tablet. It’s about smarter design. Companies are using AI to predict which drug pairs will work best-analyzing genetic data, drug interactions, and patient outcomes to find combinations that are truly synergistic. The next wave of FDCs will target rare diseases, personalized cancer therapies, and even neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s.Regulators are catching up, too. The WHO is expected to update its Essential Medicines List in 2025, adding more evidence-backed combinations and removing outdated ones. The message is clear: convenience matters, but only if it’s built on science-not sales.

For now, the rule stays simple: one pill doesn’t mean better medicine. It just means one pill. Make sure it’s the right one for you.

Nicole Ziegler

November 20, 2025 AT 03:20Michael Fessler

November 21, 2025 AT 07:30Shiv Karan Singh

November 22, 2025 AT 11:13Summer Joy

November 23, 2025 AT 15:10Kristi Bennardo

November 24, 2025 AT 15:46Alyssa Torres

November 25, 2025 AT 14:12Nosipho Mbambo

November 27, 2025 AT 12:14daniel lopez

November 27, 2025 AT 16:26Aruna Urban Planner

November 28, 2025 AT 02:31Bharat Alasandi

November 28, 2025 AT 21:45King Over

November 30, 2025 AT 19:58Katie Magnus

December 2, 2025 AT 04:06