When you’re in severe pain-after surgery, a broken bone, or a flare-up of chronic back pain-it’s tempting to reach for opioids. They work fast. They take the edge off. But for many people, what starts as short-term relief turns into something much harder to escape. The truth is, opioids aren’t the go-to solution for most types of pain. And when they’re used incorrectly, the risks can be life-changing-or fatal.

When Opioids Might Actually Help

Opioids have a place in medicine, but only in very specific situations. The CDC’s 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline makes this clear: opioids should never be the first option for chronic pain. That means pain lasting more than three months. Instead, doctors should try physical therapy, exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, or non-opioid medications like acetaminophen or NSAIDs first.

Where opioids do make sense is for short-term, severe acute pain. Think: major trauma, post-surgical recovery, or advanced cancer pain. Even then, the goal isn’t to eliminate all pain-it’s to get you through the worst few days so you can start moving and healing. The Massachusetts General Hospital guidelines say opioids should be the last choice for acute pain, not the first.

For chronic non-cancer pain, the VA/DoD guidelines are even stricter: opioids are only considered after non-drug treatments and non-opioid meds have failed. And even then, the patient must be carefully screened. If you have a history of substance use disorder, untreated depression, or severe breathing problems, opioids are usually off the table.

How Much Is Too Much?

Dosage matters more than most people realize. The CDC found that for every extra 10 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day between 20 and 50 MME, your risk of overdose goes up by 8%. Between 50 and 100 MME, that jump becomes 11%. That’s not a small increase-it’s a steep cliff.

Most guidelines agree: 50 MME per day is the upper limit for most patients. Going above 90 MME requires strong justification and extra safety steps. And if you’re on 100 MME or more? Your risk of developing an opioid use disorder jumps to about 26%, according to VA/DoD data. That’s more than one in four people.

But it’s not just about the dose. Combining opioids with benzodiazepines-medications for anxiety or sleep-multiplies the danger. The risk of overdose becomes 3.8 times higher. In some cases, it’s more than ten times higher. That’s why doctors are now trained to ask: “Are you taking anything else for sleep or anxiety?”

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone who takes opioids ends up dependent. But some people are far more vulnerable. The IHA guidelines list four clear red flags:

- Doses of 50 MME or more per day (4x higher overdose risk)

- Taking benzodiazepines at the same time (up to 10.5x higher risk)

- A history of substance use disorder (3.5x higher risk)

- Being 65 or older (slower metabolism, higher sensitivity)

Genetics also play a role. The American Society of Addiction Medicine says 40-60% of your risk for opioid use disorder is tied to your genes. That means two people on the same dose, with the same condition, can have wildly different outcomes.

And here’s something many don’t realize: the biggest risk comes in the first 90 days. That’s when most people who develop dependence start down that path. That’s why the first few weeks of treatment are critical-not just for pain control, but for watching for warning signs.

What Doctors Should Be Watching For

Good opioid therapy isn’t just about writing a prescription. It’s about ongoing monitoring. The VA/DoD guidelines require regular check-ins:

- At least every three months for stable patients

- Monthly for high-risk patients

- Pain scores (on a 0-10 scale)

- Functional improvement (can you walk? Sleep? Work?)

- Urine drug tests to check for other substances

- Screening tools like the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM)

But here’s the problem: a 2021 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found only 37% of primary care providers regularly use these tools-even though nearly all guidelines recommend them. Why? Lack of time. Lack of training. Many doctors feel unprepared to have these tough conversations.

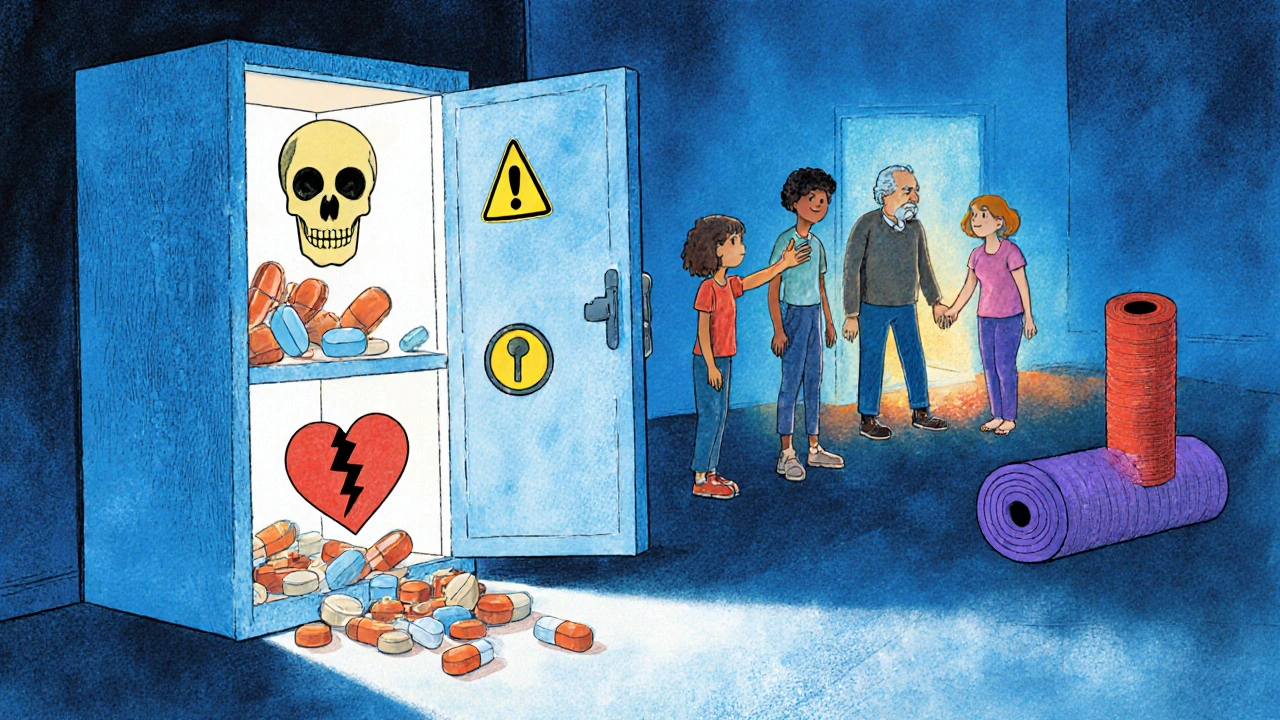

And then there’s the issue of leftover pills. A Kaiser Permanente study showed that 43% of patients prescribed opioids for acute pain get more tablets than they need. And 76% of those unused pills sit in medicine cabinets, where kids, teens, or visitors might find them. That’s not just waste-it’s a public health hazard.

What Happens When You Need to Stop?

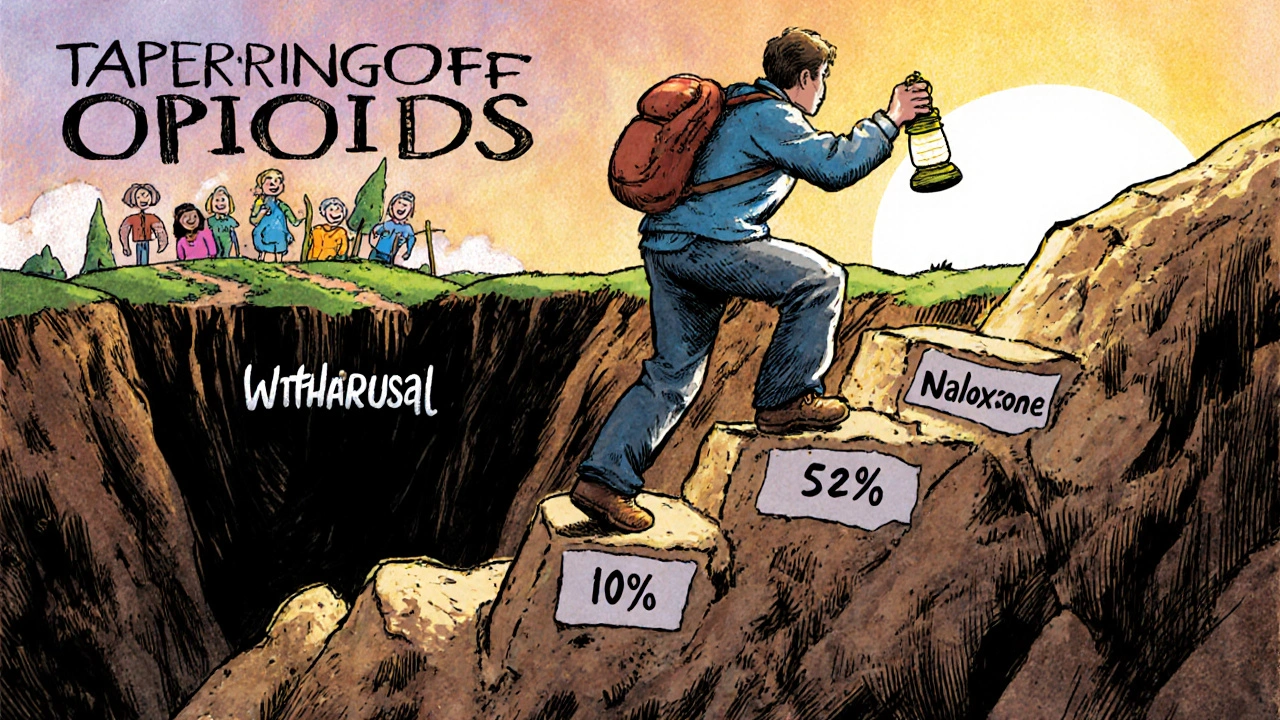

Stopping opioids isn’t as simple as “just quit.” Your body adapts. If you stop suddenly, you can get severe withdrawal: nausea, sweating, muscle cramps, insomnia, anxiety. Worse, research shows abrupt discontinuation can push people toward illegal opioids like heroin or fentanyl.

That’s why tapering matters. The Kaiser Permanente guideline recommends different speeds based on your situation:

- Slow taper: 2-5% reduction every 4-8 weeks (for stable users with good function)

- Moderate taper: 5-10% every 4-8 weeks (if pain isn’t improving or tolerance is rising)

- Rapid taper: 10% per week (only if risks outweigh benefits-like doses over 90 MME or dangerous side effects)

The key? It’s not one-size-fits-all. You and your doctor need to decide together. The CDC warns against forcing patients off opioids too fast. Many people have been on them for years-suddenly cutting them can do more harm than good.

The Bigger Picture: What’s Changing?

Prescribing habits are shifting. In 2012, U.S. doctors wrote 81.3 opioid prescriptions per 100 people. By 2020, that number had dropped to 46.7-a 42.5% decline. That’s progress. But overdose deaths are still high: over 80,000 in 2021. Why? Because fentanyl and other synthetic opioids have flooded the market. Many people who started with prescription pills now use street drugs they don’t understand.

More hospitals now carry naloxone-a drug that can reverse an overdose-in their emergency rooms and clinics. In 2016, only 18% did. Now it’s 51%. Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) are also more widely used. In 49 states, doctors check these databases before writing an opioid prescription. That helps catch people who are “doctor shopping” for pills.

And research is moving forward. The NIH’s HEAL Initiative has poured $1.5 billion into finding non-addictive pain treatments. Right now, 37 new non-opioid drugs are in late-stage trials. The goal isn’t just to reduce opioids-it’s to replace them with safer, more effective options.

What You Should Do If You’re on Opioids

If you’re currently taking opioids for pain:

- Ask your doctor: “Is this still helping me function better?”

- Don’t take more than prescribed-even if the pain comes back.

- Keep your pills locked up. Never share them.

- Ask if you should have naloxone on hand.

- Report any signs of dependence: needing higher doses, cravings, mood changes, or using pills for reasons other than pain.

- Explore alternatives: physical therapy, acupuncture, mindfulness, or nerve blocks.

If you’re worried about dependence, you’re not alone. And you’re not weak. This isn’t a moral failing-it’s a medical issue. The best thing you can do is talk to your doctor. Don’t wait until it’s too late.

What You Should Do If You’re Not on Opioids

If you’ve been prescribed opioids in the past-or know someone who has-remember this: pain doesn’t always need a pill. Many people find relief through movement, therapy, heat, ice, or even just good sleep. Don’t assume opioids are the only way. Ask your doctor: “What else can I try first?”

Are opioids ever safe for long-term pain?

Opioids can be used long-term for some people with severe chronic pain, but only after other treatments have failed and under strict monitoring. Most guidelines recommend keeping daily doses below 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME). Long-term use carries high risks of dependence, tolerance, and overdose. The evidence shows modest pain relief at best, with diminishing returns over time.

Can you become dependent even if you take opioids exactly as prescribed?

Yes. Physical dependence-where your body adapts to the drug-is common with long-term use, even when taken exactly as directed. This is different from addiction, which involves compulsive use despite harm. About 8-12% of patients on chronic opioid therapy develop opioid use disorder. Risk increases sharply above 50 MME per day and with certain genetic or psychological factors.

Why do doctors sometimes prescribe too many opioid pills?

Many prescriptions are written based on outdated habits or patient expectations. A common practice was to hand out 30 tablets for a 7-day recovery, even when only 5-10 were needed. This creates excess pills that can be misused or diverted. Modern guidelines now recommend prescribing the smallest effective amount-often just enough for a few days.

What’s the difference between dependence and addiction?

Dependence means your body has adapted to the drug and will experience withdrawal if you stop. Addiction is a brain disorder characterized by loss of control, cravings, continued use despite harm, and compulsive behavior. You can be dependent without being addicted. But addiction often starts with dependence. That’s why careful monitoring is so important.

Is naloxone only for people who use street drugs?

No. Naloxone is recommended for anyone on opioids at doses of 50 MME or higher, especially if they also take benzodiazepines, have a history of substance use, or are over 65. Even people taking opioids exactly as prescribed can accidentally overdose-especially if they combine them with alcohol or sleep aids. Having naloxone on hand is a safety net, not a sign of failure.

What are the best alternatives to opioids for chronic pain?

Evidence-backed alternatives include physical therapy, exercise programs (like tai chi or swimming), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), acupuncture, and certain non-opioid medications like gabapentin or duloxetine. For some, nerve blocks or spinal cord stimulation help. The key is finding a combination that improves function-not just numbing pain. Many people find they can reduce or eliminate opioids by focusing on movement and mental health.

Final Thoughts

Opioids aren’t evil. They’re powerful tools-like a chainsaw. Useful in the right hands, dangerous in the wrong ones. The goal isn’t to eliminate them entirely. It’s to use them wisely: only when needed, at the lowest effective dose, for the shortest time possible. And always, always with a plan to get off them safely.

Pain is real. So is the risk. The best care doesn’t come from a pill bottle. It comes from honest conversations, careful monitoring, and a willingness to try other paths first.

Neoma Geoghegan

November 24, 2025 AT 00:19Opioids are a tool, not a crutch. If you're hitting 50+ MME and still can't walk, something's broken in the plan. Time to pivot to PT or CBT before it's too late.

Bartholemy Tuite

November 24, 2025 AT 08:05Man i remember when my cousin got 120 MME after a back surgery and they just handed him a bottle like it was ibuprofen. No followup, no screening, just 'here ya go'. Now he's on methadone and his kid's in foster care. This post? 10/10. We need to stop treating pain like a vending machine.

Sam Jepsen

November 25, 2025 AT 14:25Big shoutout to the docs who are actually following the guidelines. I had a pain specialist who made me do yoga, track my sleep, and only gave me 7 pills for a month. I didn't need more. We can do better than pills.

Yvonne Franklin

November 25, 2025 AT 17:24Dependence isn't addiction but it's still real. I was on 30 MME for 6 months after a fusion. Stopped cold turkey. Withdrawal was hell. Tapering saved me. Don't underestimate the body's adaptation.

Melvina Zelee

November 27, 2025 AT 11:02it's wild how we treat pain like it's a bug to be fixed with one button but the body's a whole system. if you're not moving, sleeping, or feeling connected, no pill fixes that. we need to stop chasing numbness and start building resilience

ann smith

November 29, 2025 AT 03:04Thank you for this. 💙 As someone who's seen loved ones struggle, I'm so glad we're finally shifting toward care over pills. Naloxone should be as common as smoke detectors. 🙏

Julie Pulvino

November 30, 2025 AT 08:37I used to think opioids were the answer until I saw my dad go from walking to bed-bound on 80 MME. He didn't even need them anymore. But he was scared to stop. The fear of pain is worse than the pain sometimes. Tapering with support? Life-changing.

Patrick Marsh

December 1, 2025 AT 05:02Warning: Combining opioids with benzodiazepines? 3.8x overdose risk. That’s not a suggestion. That’s a red flag. Always ask. Always check. Always document.

Danny Nicholls

December 2, 2025 AT 01:46My uncle took 100 MME for 2 years after a car crash. He didn't get addicted... but he lost his job, his marriage, and his motivation. Pain meds don't fix your life. Movement, therapy, and community do. 🙌

Mark Williams

December 2, 2025 AT 09:21Genetics account for 40–60% of OUD risk? That’s huge. We need pharmacogenomic screening before prescribing. Not just ‘do you have a history?’-but ‘what’s your CYP2D6 profile?’ This isn’t sci-fi-it’s clinical reality.

Daniel Jean-Baptiste

December 3, 2025 AT 08:21leftover pills are a silent epidemic. my mom had 47 pills left after knee surgery. she just left them in the bathroom. my cousin took 2. ended up in rehab. if we prescribed less, fewer people get hooked by accident

luke young

December 4, 2025 AT 13:10the chainsaw analogy? Perfect. I’ve used one before-know when to turn it off. Opioids are the same. Don’t keep running it just because it’s there.

james lucas

December 5, 2025 AT 13:18so many docs still think if you're not screaming you're fine. but pain isn't about noise. it's about function. can you hold your grandkid? can you sleep through the night? can you go to work without feeling like you're dragging a corpse? those are the real metrics. not the 1-10 scale. that's useless. i had a dr who asked me those questions and i cried because no one ever had before. we need more of them. not more pills. just more care.