When you hear the word radiation, you might think of nuclear accidents or X-ray machines at the dentist. But for millions of people with cancer, radiation is a precise, life-saving tool. Radiation therapy doesn’t just zap tumors-it breaks them down from the inside by targeting the very thing that makes cancer cells dangerous: their DNA.

How Radiation Kills Cancer Cells

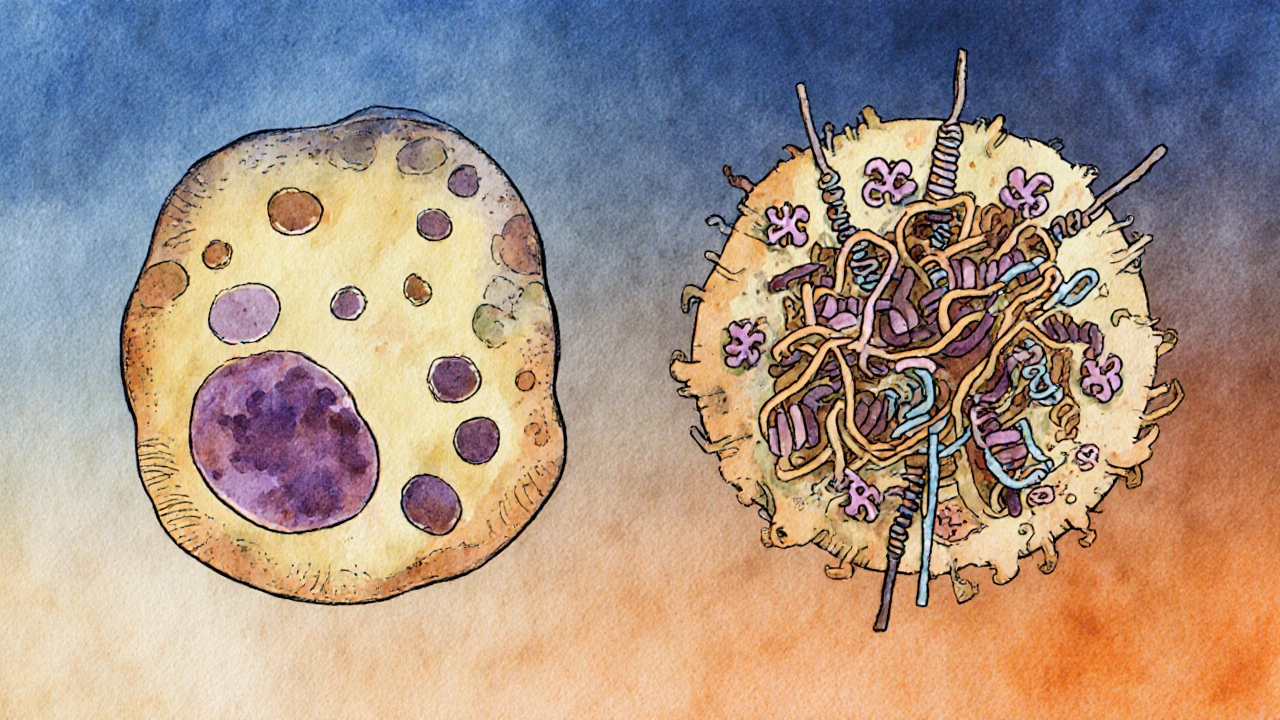

Radiation therapy uses high-energy particles or waves-like X-rays or protons-to damage the DNA inside cancer cells. This isn’t random destruction. It’s targeted. The goal is to deliver enough energy to break the DNA strands so badly that the cell can’t repair itself and dies. The most lethal kind of damage is a double-strand break. Imagine your DNA as a twisted ladder. Normally, if one side snaps, the cell can use the other side as a template to fix it. But when both sides break at the same time, the cell loses its blueprint. That’s where things fall apart. This damage doesn’t happen instantly. Radiation creates reactive oxygen species (ROS) inside the cell. These are like molecular grenades-unstable molecules that rip through proteins, lipids, and DNA. The result? Oxidative stress that overwhelms the cell’s defenses.The Two Main Ways Cells Die After Radiation

Not all cancer cells die the same way. There are two primary paths:- Apoptosis: The cell self-destructs in a controlled, orderly way. Think of it as the cell hitting the emergency shutdown button. This happens in some cell types, especially when the p53 gene is active. p53 is often called the “guardian of the genome”-it detects DNA damage and triggers cell death if the damage is too severe.

- Reproductive failure: This is the most common way radiation kills cells. The cell doesn’t die right away. It tries to divide, but with broken DNA, it can’t copy its chromosomes properly. The result? A messy, failed cell division. The cell either dies during the process or becomes so unstable it can’t survive the next cycle. This is especially effective in fast-growing tissues like the lining of the gut or bone marrow.

How Cells Try to Repair the Damage (And Why That Matters)

Cancer cells aren’t helpless. They have repair crews. When radiation breaks DNA, two main systems kick in:- Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ): A quick-and-dirty fix. The cell glues the broken ends back together, even if it’s messy. It’s fast but error-prone. This often leads to mutations or cell death.

- Homologous recombination (HR): A precise repair method. The cell uses a healthy copy of DNA (from a sister chromosome) as a template to fix the break perfectly. This is how healthy cells survive radiation-and how some cancer cells cheat death.

The Role of Oxygen and the Tumor Environment

Radiation works best when there’s plenty of oxygen. Why? Because oxygen helps create the reactive molecules that damage DNA. Tumors often have low-oxygen areas-called hypoxic zones-where radiation is up to three times less effective. This is one reason why some tumors resist treatment. If a cancer cell is buried deep in a low-oxygen part of the tumor, it can survive radiation that kills cells nearby. Researchers are testing ways to boost oxygen delivery or use drugs that mimic oxygen’s effects to make radiation work better in these areas. The tumor environment itself also plays a role. Surrounding cells-like fibroblasts and immune suppressors-can shield cancer cells or even help them repair DNA. In about 60% of solid tumors, these surrounding cells contribute to treatment resistance.The Ceramide Pathway: A Hidden Killer

There’s another mechanism you won’t hear about often: ceramide. When radiation hits a cell, it activates an enzyme called acid sphingomyelinase. This enzyme turns a fat molecule in the cell membrane into ceramide-a signaling molecule that triggers apoptosis. Ceramide doesn’t just act in the cancer cell. It also damages the blood vessels feeding the tumor. High-dose radiation, like in SBRT (stereotactic body radiation therapy), causes these vessels to leak and collapse. The tumor starves. Cells die from lack of oxygen and nutrients days after the radiation is done. This delayed effect is why some patients see tumor shrinkage weeks after treatment ends.How Radiation Makes Cancer Visible to the Immune System

Radiation doesn’t just kill. It also exposes. When cancer cells die from radiation, they release proteins and fragments that the immune system recognizes as foreign. Normally, tumors hide from immune cells by suppressing signals. But radiation changes that. It increases the number of tumor antigens presented on the cell surface, making cancer cells easier for T-cells to spot. Studies show radiation can boost the effectiveness of immunotherapy drugs like pembrolizumab. In one trial, combining radiation with immunotherapy raised the response rate in lung cancer patients from 22% to 36%. That’s not just a small improvement-it’s a game-changer.

Why Some Tumors Don’t Respond

Despite all this, about 30-40% of tumors don’t respond well to radiation. Why?- Enhanced DNA repair: Some tumors overproduce repair proteins like 53BP1. Patients with high levels of this protein have worse outcomes after radiation.

- Cell cycle changes: Cancer cells can pause their growth to avoid radiation damage during vulnerable phases.

- Survival pathway activation: Tumors can turn on genes like AKT or NF-kB that block apoptosis and help them survive.

The Future: FLASH, AI, and Personalized Dosing

New techniques are changing the game.- FLASH radiotherapy delivers radiation in less than a second-at speeds over 40 Gy per second. Early results show it kills tumors just as well but spares healthy tissue. Human trials started in 2020.

- AI-powered planning now designs treatment plans in under 10 minutes, compared to hours before. This means more precise doses, fewer side effects, and faster treatment starts.

- Personalized dosing is on the horizon. Instead of giving everyone the same dose, doctors may soon use genetic tests to predict how a tumor will respond and adjust radiation levels accordingly.

What This Means for Patients

Radiation therapy isn’t magic. It’s science-deep, complex, and constantly improving. Understanding how it works helps patients make better choices. If you’re considering radiation:- Ask if your tumor has BRCA or other DNA repair mutations-these could make you a candidate for combination therapy.

- Find out if your center uses IMRT or SBRT. These techniques reduce damage to healthy tissue.

- Ask about clinical trials combining radiation with immunotherapy or PARP inhibitors.

How long does it take for radiation to kill cancer cells?

Radiation doesn’t kill cancer cells immediately. Most die over days or weeks as they try to divide with damaged DNA. Some die during treatment through apoptosis, but the majority fail to replicate properly during cell division. The full effect of radiation therapy often becomes visible on scans weeks after treatment ends.

Does radiation therapy hurt?

No, the actual radiation treatment is painless. You won’t feel heat, tingling, or shock during the session. However, side effects like skin redness, fatigue, or soreness in the treated area can develop over time. These are not from the radiation itself, but from how your healthy tissues respond to the treatment.

Can radiation therapy cure cancer?

Yes, for many types of cancer, radiation can be curative-especially when the tumor is localized. For example, early-stage prostate, head and neck, or cervical cancers are often cured with radiation alone. Even in advanced cases, radiation can shrink tumors, relieve symptoms, and extend life.

Why do some cancer cells survive radiation?

Some cancer cells survive because they’re better at repairing DNA damage, live in low-oxygen areas, or have mutations that block cell death signals. Tumors with high levels of repair proteins like 53BP1 or those that activate survival pathways like AKT are more likely to resist treatment. This is why combination therapies are becoming standard.

Is radiation therapy safe for healthy tissue?

Modern techniques like IMRT and SBRT focus radiation with sub-millimeter accuracy, sparing nearby organs. Healthy cells can repair radiation damage better than cancer cells because they have intact DNA repair systems. Side effects happen, but they’re usually temporary and manageable. FLASH radiotherapy may reduce these even further in the near future.

Can radiation therapy be used more than once?

Yes, but it depends on the area treated and the total radiation dose received. Healthy tissues have limits to how much radiation they can handle. If cancer returns in the same spot, doctors may use different techniques, lower doses, or combine radiation with other treatments to avoid overexposure.

Wendy Edwards

November 26, 2025 AT 10:00Ryan C

November 28, 2025 AT 05:33Dan Rua

November 30, 2025 AT 05:08Mqondisi Gumede

November 30, 2025 AT 12:53Douglas Fisher

December 1, 2025 AT 10:56Amanda Meyer

December 2, 2025 AT 01:20hannah mitchell

December 3, 2025 AT 18:22Vanessa Carpenter

December 5, 2025 AT 08:21stephen riyo

December 7, 2025 AT 03:50