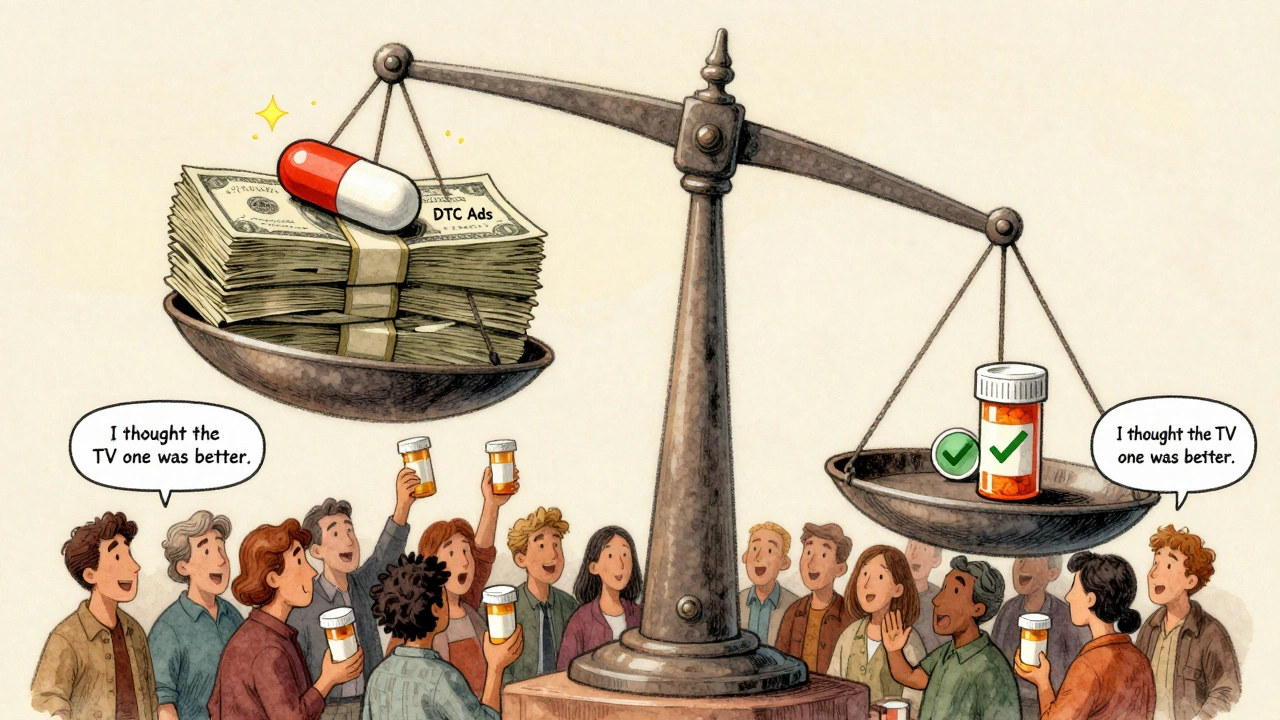

When you see a TV ad for a new cholesterol drug with a sunny beach, laughing family, and soothing voiceover saying, "Don’t let high cholesterol hold you back," you might not realize you’re being sold more than a pill-you’re being sold a brand. And that brand doesn’t just compete with other branded drugs. It competes with something far cheaper, just as effective, and sitting right on the pharmacy shelf: the generic version.

In the United States, direct-to-consumer (DTC) drug advertising is a $6.58 billion-a-year industry. It’s legal here and in New Zealand-only two countries in the world that allow it. These ads don’t just inform. They shape what patients ask for, what doctors prescribe, and how people think about generic medications. And the results aren’t always what you’d expect.

Ads Don’t Just Sell Branded Drugs-They Change How People See Generics

Most people assume that if an ad promotes a branded drug like Lipitor, it only boosts sales of Lipitor. But research from the Wharton School shows something more subtle: when patients see an ad for a branded statin, they often end up taking a generic statin instead. Why? Because they walk into the doctor’s office asking for "that cholesterol medicine," and the doctor, knowing generics are just as effective, prescribes the cheaper version. This is called the "spillover effect."

Here’s the twist: while advertising increases overall use of cholesterol-lowering drugs-including generics-it also makes people believe the branded version is better. Even when they end up with the generic, they’re more likely to think, "I wish I could’ve gotten the real one," or "This isn’t the same as the one on TV." That belief isn’t based on science. It’s based on emotion.

Pharmaceutical companies know this. Their ads aren’t designed to teach. They’re designed to trigger desire. Scenes of people hiking, dancing, or playing with grandchildren. Soft music. A doctor smiling. A tiny disclaimer at the bottom: "Possible side effects include muscle pain, liver issues, and increased risk of diabetes." Most viewers don’t remember the risks. They remember the feeling.

Patients Ask for Ads, Doctors Often Give In

It’s not just patients who are influenced. Doctors are too. A 2005 study in JAMA found that when patients requested a specific drug by name-even if it wasn’t the best choice-the doctor prescribed it 70% of the time. That number jumped even higher when the request came from someone who’d seen an ad.

One study of 108 patient requests for medications that doctors considered inappropriate found that 75 of them were filled. That’s 69%. These weren’t edge cases. These were routine visits. A patient says, "I saw an ad for this new diabetes pill," and the doctor, under time pressure, with no alternative treatment plan ready, writes the script. The patient leaves happy. The pharmacy fills it. The drug company makes money. And the generic version? It never even got a chance.

It’s not that doctors don’t know generics work. They do. But when a patient walks in with a script from a TV ad, it’s harder to say no. Especially when the patient says, "My friend is on it and she’s doing great." That’s social proof. And it’s powerful.

Generics Are Just as Good-But Ads Make Them Feel Like Second Choice

Generic drugs are chemically identical to their branded counterparts. They have the same active ingredients, the same dosage, the same safety profile. The only differences? The color, shape, and price. Generics cost 80-85% less on average. And yet, because they’re rarely advertised, they’re seen as inferior.

Think about it: you’ve seen dozens of ads for brand-name antidepressants. You’ve never seen one for fluoxetine-the generic version. Even though fluoxetine is the exact same drug as Prozac. Same molecule. Same effect. Same side effects. But Prozac has a story. A face. A lifestyle. Fluoxetine? Just a label on a bottle.

That’s not an accident. It’s strategy. Pharmaceutical companies spend billions on branding because it works. A 2020 analysis found that for every dollar spent on DTC ads, companies got back more than $4 in sales. That’s a return most marketers would kill for. And it’s not because the drugs are better. It’s because the ads made people believe they were.

Repeated Exposure Doesn’t Mean Better Understanding

The FDA studied how people process information in drug ads. They found that even after watching an ad four times, most people still couldn’t accurately recall the risks. Benefits? A little better remembered. But risks? Almost always forgotten. And that’s dangerous.

When an ad says, "This drug can help you feel like yourself again," it’s easy to hear that. But when it says, "May cause severe muscle damage, kidney failure, or depression," you tune out. The brain filters out the scary stuff. That’s why generics get the short end of the stick: they don’t get the benefit-heavy ads. So people assume they’re riskier-or less effective.

Even when patients do understand the science, the emotional weight of branding overrides logic. A 2018 FDA study showed that exposure frequency didn’t improve how people judged the likelihood or severity of side effects. More ads didn’t make people smarter. It just made them more familiar with the brand name.

The Real Cost: More Spending, Less Health

More ads mean more prescriptions. But not necessarily better outcomes. Research shows that patients who start taking a drug because of an ad are actually less likely to stick with it long-term. Why? Because their motivation isn’t health-it’s marketing. They saw a happy person on TV. They wanted to feel that way. But when the initial excitement fades, so does the commitment.

And here’s the kicker: those new patients often don’t need the drug at all. A 2023 study found that 70% of the increase in prescriptions from advertising came from people starting treatment who wouldn’t have otherwise. Only 30% were existing patients taking it more consistently. That means most of the spending from ads goes to people who don’t need the drug-or who would’ve done just as well with lifestyle changes.

Meanwhile, the cost of all this? Billions. The U.S. spends more on prescription drugs per person than any other country. And a big chunk of that is because of ads pushing branded drugs over generics. If patients took generics as often as they should, the system could save tens of billions a year.

What Can You Do?

You don’t have to avoid ads. But you do need to question them.

- When you see an ad, ask: "Is this the only option?" Check with your pharmacist. Generics are often listed right next to the brand name.

- Ask your doctor: "Is there a generic version? Is it right for me?" Don’t let the brand name on the screen dictate your treatment.

- Remember: the drug on TV isn’t the only one that works. It’s just the one with the best marketing.

Generics aren’t cheap because they’re bad. They’re cheap because they’re old. And that’s exactly why they’re safe, proven, and effective. The science hasn’t changed. The ads have.

Why New Zealand Is Watching Closely

While the U.S. runs full-throttle on DTC advertising, New Zealand has its own version-less aggressive, but still present. Here, ads can’t make claims without evidence, and they must include risk information. But even here, the same psychological effects are visible. Patients ask for branded drugs they’ve seen on TV. Pharmacists get asked why their generic looks different. Doctors get pressured to prescribe what’s on screen, not what’s best.

It’s a warning. Even with stricter rules, advertising still shapes perception. And perception drives behavior. The question isn’t whether ads work. They clearly do. The question is: at what cost?

When you choose a generic, you’re not choosing second best. You’re choosing the same medicine, for a fraction of the price. And that’s not just smart. It’s powerful.

Are generic drugs really the same as brand-name drugs?

Yes. Generic drugs contain the same active ingredients, in the same strength and dosage form, as their brand-name counterparts. They must meet the same FDA standards for safety, effectiveness, and quality. The only differences are in inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes), packaging, and price. Generics cost 80-85% less on average.

Why do doctors prescribe branded drugs when generics are available?

Sometimes it’s because the patient asked for it. Studies show that when patients request a specific brand name-often because they saw an ad-doctors are far more likely to prescribe it, even if a generic would work just as well. Time pressure, lack of alternatives, or fear of patient dissatisfaction can also play a role.

Do drug ads increase adherence to medication?

Slightly-for existing patients. Research shows a 10% increase in advertising leads to only a 1-2% increase in adherence among people already taking the drug. But for new patients who start because of an ad, adherence is actually lower. Their motivation is often emotional, not medical, so they’re more likely to stop when the initial excitement fades.

Why don’t generic drugs have ads?

Because there’s little financial incentive. Once a drug goes generic, multiple companies sell it. No single company owns the brand, so no one wants to pay for ads that benefit competitors. The original brand-name maker stops advertising once generics enter the market. So the public sees no ads for generics-only for the branded versions they replaced.

Is it safe to switch from a brand-name drug to a generic?

Yes, for the vast majority of medications. The FDA requires generics to be bioequivalent, meaning they work the same way in the body. There are rare exceptions-like certain seizure or thyroid medications-where small differences in absorption matter. But your doctor or pharmacist will let you know if that applies to your case. For most drugs, switching is not only safe-it’s smart.

What’s the impact of DTC advertising on healthcare costs?

It drives costs up significantly. For every dollar spent on DTC advertising, pharmaceutical companies get back over $4 in sales. Much of that comes from patients choosing more expensive branded drugs over cheaper generics. Studies estimate that if generic use increased by just 10%, the U.S. could save $10-$20 billion annually. Advertising doesn’t just influence choices-it changes the economics of care.

Webster Bull

December 13, 2025 AT 14:19Generics are the real MVPs and nobody talks about it. End of story.

kevin moranga

December 13, 2025 AT 23:27You know what kills me? I used to think generics were "second-rate" until my cousin switched from Lipitor to atorvastatin and saved $200 a month-same bloodwork, same energy, no side effects. The only difference? The pill’s blue instead of purple. Pharma companies don’t want you to know that the brand name is just a fancy label on the same chemistry. They’re selling a dream, not a drug. And honestly? That’s not just unethical-it’s exploitative. We’re conditioned to equate price with quality, but in medicine, that’s a dangerous myth. The FDA doesn’t play games. If it’s approved as generic, it’s got the same active ingredients, same absorption rates, same everything. The color? The shape? The logo on the bottle? Pure marketing fluff. I’ve seen doctors roll their eyes when patients beg for the TV drug. They know. They just get pressured into it. And guess who pays? Us. Through higher premiums, higher copays, and a system that rewards advertising over actual health outcomes. It’s insane. We need to rewire how we think about meds. Not every solution needs a jingle and a family dancing on a beach. Sometimes, the best medicine is the one that doesn’t try to sell you a lifestyle.

Donna Hammond

December 15, 2025 AT 23:18I’m a pharmacist with 18 years in community practice, and I can confirm: 95% of the time, generics are indistinguishable from brand-name drugs in real-world use. The exceptions? A tiny fraction of medications where bioavailability is extremely narrow-like warfarin or levothyroxine-and even then, switching within the same generic manufacturer usually works fine. The real issue isn’t science-it’s perception. Patients will say, "This generic doesn’t work like the other one," but when we check the bottle, it’s the same manufacturer, same batch code, just different packaging. The mind does weird things when branding is involved. I’ve had people cry because they couldn’t get "the red pill" anymore. I hand them the generic, explain the science, and they walk out relieved. But the damage? It’s already done. They think they’re getting less. And that belief can affect adherence. We need better public education, not more ads. The FDA’s warnings are buried under 10 seconds of piano music and a golden retriever.

Lauren Scrima

December 17, 2025 AT 05:23So let me get this straight: we spend billions on ads so people will feel bad about taking a $4 pill that works just as well? Brilliant. Just brilliant. 😒

Harriet Wollaston

December 18, 2025 AT 02:04I’m from a family that’s been on generics for decades-my grandma took generic metformin for 20 years. She lived to 94. Never once complained about the pill being "not the real thing." We didn’t have money for brand names, but we had science. And that was enough. It breaks my heart that now, people think if it’s not on TV, it’s not valid. We’ve lost touch with the idea that medicine doesn’t need a Hollywood producer to be effective. My mom still says, "If it’s in the same bottle as the brand, it’s the same medicine." Simple. True. And way too rare these days.

Hamza Laassili

December 18, 2025 AT 03:15BRAND NAMES = TRUST. GENERICS = CHEAP JUNK. AMERICA DON'T DO THAT. WE PAY FOR THE BEST. WHY? BECAUSE WE CAN. AND WE SHOULD. STOP LETTING BIG PHARMA PUSH THEIR CRAP ON US. BUY THE ADVERTISED ONE. YOU DESERVE IT. 🇺🇸

Scott Butler

December 18, 2025 AT 11:39What’s next? Ads for toilet paper telling you the generic doesn’t clean as well? This is why America’s healthcare is a joke. You want a drug that works? Pay for the one with the fancy commercial. If you’re too cheap to afford the real thing, maybe you shouldn’t be on meds at all. Stop whining about ads-they’re just telling you what’s good. And if you can’t afford it, go to a clinic. Don’t blame the system for your budget.

Richard Ayres

December 18, 2025 AT 18:51It’s fascinating how deeply marketing influences our perception of value-even in areas where objective quality is identical. The emotional weight attached to brand names isn’t irrational; it’s a byproduct of decades of conditioning. We associate familiarity with safety, and advertising creates that familiarity without requiring understanding. The real tragedy is that this dynamic undermines trust in science. When people believe a generic is inferior because it lacks a jingle, they’re not rejecting the drug-they’re rejecting the absence of narrative. Maybe the solution isn’t banning ads, but mandating equal-time public service campaigns that explain bioequivalence in the same emotional language: "This is your medicine. This is your health. This is your power." We need stories too-but ones that empower, not manipulate.

sharon soila

December 19, 2025 AT 23:48Let me tell you something simple. A drug is a drug. It does what it does. The brand name is just a name. The generic is the same thing, cheaper. That’s it. No magic. No secrets. Just math. And if you choose the expensive one because of a TV ad, you’re not being loyal-you’re being played. The people who make these ads don’t care if you live longer. They care if you buy more. And the system lets them. So next time you see that smiling family on the beach, ask yourself: Who’s really dancing here? And who’s paying the bill?

Bruno Janssen

December 20, 2025 AT 12:38I used to take the brand. Then I switched. Didn’t feel different. But I kept thinking I should’ve stayed on it. Like I missed out on something. Even though I knew it was the same. It’s weird. The ad didn’t lie. But it made me feel like a failure for choosing the cheaper one. I don’t even know why I’m telling you this. I just… needed to say it.

Emma Sbarge

December 22, 2025 AT 02:13My doctor told me to switch to generic lisinopril after I’d been on the brand for three years. I cried. Not because I was sick-because I felt like I’d been betrayed. Like the pill I trusted had been swapped out for a knockoff. Turns out? Same exact molecule. Same results. I just needed to unlearn the lie that price equals quality. It’s not just about money. It’s about dignity. We’re taught to equate cost with care. But sometimes, the most caring choice is the quiet one-the one without the ad.