Human papillomavirus, or HPV, isn’t just another virus. It’s the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world, and for many people, it causes no symptoms at all. But for some, it can quietly lead to cancer-especially cervical cancer. The good news? We now have powerful tools to stop it before it starts: vaccines, smarter screening, and clear guidelines that work. This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening right now, and it’s saving lives.

What HPV Actually Does

There are more than 200 types of HPV, but only about 14 are considered high-risk. Among them, types 16 and 18 are the most dangerous-they cause about 70% of all cervical cancers. These viruses don’t just show up and vanish. If your immune system doesn’t clear them within a couple of years, they can stick around, slowly changing the cells in your cervix. Over 10 to 20 years, those changes can turn into precancerous lesions, then invasive cancer.

But here’s the key point: HPV infection is not the same as cervical cancer. Most people clear the virus naturally. The problem arises when it lingers. That’s why early detection and prevention matter so much. And that’s why vaccination and screening are two sides of the same coin.

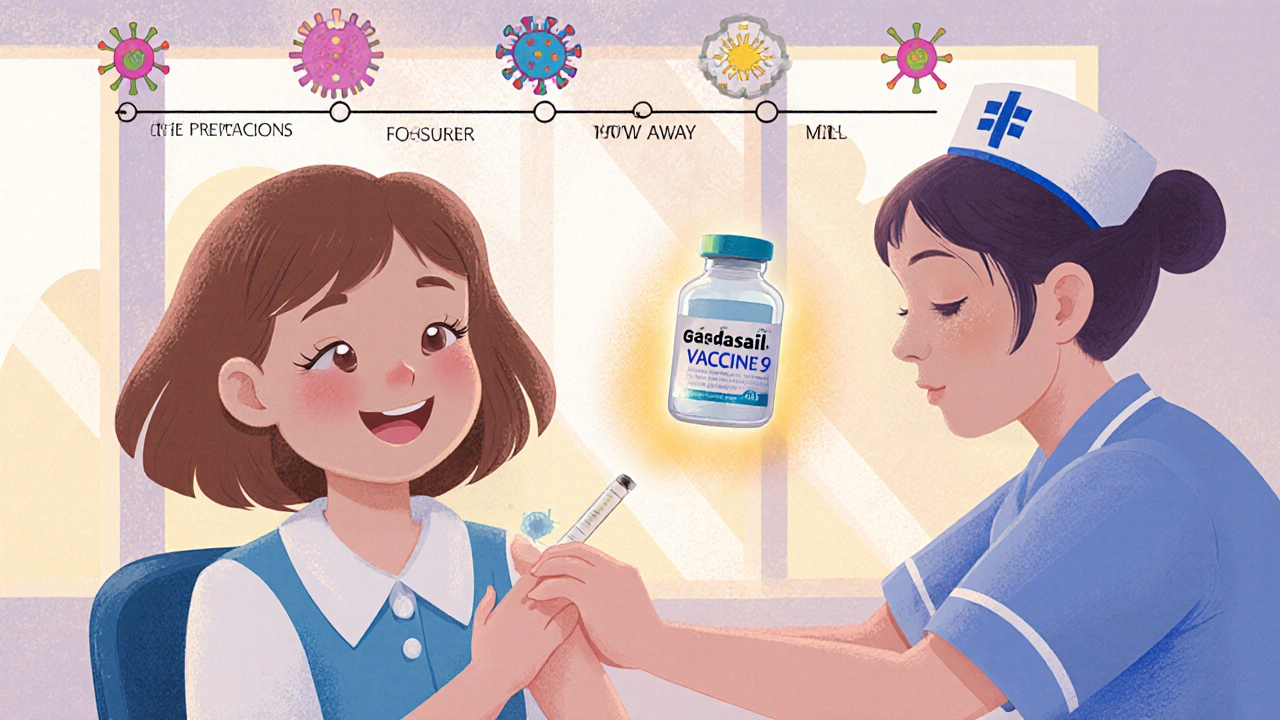

The HPV Vaccine: A Game-Changer

The first HPV vaccine, Gardasil, got FDA approval in 2006. Since then, we’ve had better versions-Gardasil 9, which protects against nine strains of HPV, including the two most dangerous ones. It’s not just for girls. Boys get it too. Why? Because HPV causes cancers in men too-anal, throat, and penile cancers. Vaccinating both genders cuts transmission and protects everyone.

The best time to get vaccinated is before exposure. That’s why health organizations recommend the vaccine for kids aged 11 to 12. Two doses are enough if started before age 15. If you’re older than 15, you’ll need three doses. But even if you’re 26 or 30, it’s still worth it. The vaccine works if you haven’t been exposed to all the strains it covers.

Real-world data shows it’s working. In countries like Australia, where vaccination rates are high, cervical precancers in young women have dropped by over 85%. In the U.S., HPV infections in teen girls fell by 88% between 2006 and 2018. This isn’t theoretical. It’s measurable. And it’s preventing cancer before it starts.

Screening: From Pap Smears to HPV Tests

For decades, the Pap smear was the gold standard. A doctor scraped cells from your cervix and looked for abnormalities under a microscope. It saved millions of lives. But it wasn’t perfect. It missed a lot of early changes. That’s why screening has shifted.

Today, the preferred method for most adults is primary HPV testing. Instead of looking at cells, labs test for the virus itself. They check for 14 high-risk types-especially 16 and 18. Two FDA-approved tests are widely used: the cobas HPV Test and the Aptima HPV Assay. Both are highly accurate and can be done with the same sample as a Pap test.

Why is this better? Because HPV testing is more sensitive. A 2018 study in JAMA found it catches 94.6% of serious precancers, while Pap smears only catch 55.4%. That’s a huge difference. It means fewer cancers slip through the cracks.

Who Gets Screened and When

Screening guidelines changed in 2020 and 2021. Here’s what you need to know:

- Ages 21-29: Pap test every 3 years. HPV testing isn’t recommended alone here because infections are common and usually clear on their own.

- Ages 25-65: Primary HPV test every 5 years. This is now the preferred method by the American Cancer Society and many U.S. health systems.

- Ages 30-65: You have three options: HPV test every 5 years, Pap test every 3 years, or both (cotesting) every 5 years. HPV testing alone is slightly more effective.

Even if you’ve been vaccinated, you still need screening. The vaccine doesn’t protect against all cancer-causing HPV types. And not everyone got vaccinated as a child. Screening isn’t optional-it’s essential.

The Rise of Self-Collected Tests

One of the biggest barriers to screening? Discomfort, fear, or lack of access. Many women avoid pelvic exams. That’s why self-collected HPV tests are a breakthrough.

Now, you can swab your own vagina at home-just like a pregnancy test-and send it to a lab. Studies show these tests are almost as accurate as those done by a clinician. Kaiser Permanente started offering them in January 2024. In Australia and the Netherlands, self-collection boosted screening rates by 30-40% among women who hadn’t been screened in years.

It’s not just convenient. It’s life-saving. The CDC says about 30% of cervical cancers happen in women who’ve never been screened. Self-collection removes one of the biggest obstacles.

What Happens If the Test Is Positive?

A positive HPV test doesn’t mean you have cancer. It means the virus is there. What happens next depends on the type.

If you test positive for HPV 16 or 18, you’ll be referred for a colposcopy-a closer look at your cervix. If you test positive for other high-risk types, you’ll usually get a Pap test too. If both are abnormal, you’ll need a colposcopy. If they’re normal, you’ll be retested in a year.

This step-by-step approach prevents over-treatment. Not every HPV infection needs surgery. Most resolve on their own. The goal isn’t to panic-it’s to monitor and act only when needed.

Global Progress and Persistent Gaps

The World Health Organization set a bold goal in 2020: eliminate cervical cancer by 2050. To get there, they want 90% of girls vaccinated by 15, 70% of women screened by 35 and 45, and 90% of abnormal cases treated.

High-income countries like the U.S., Canada, and Australia are on track. But globally, only 19% of women in low-income countries have ever been screened. That’s why self-collection and low-cost HPV tests are being rolled out in places like Kenya and India. Simple tools, big impact.

In the U.S., disparities remain. Black women are 70% more likely to die from cervical cancer than white women. That’s not biology-it’s access. Lack of insurance, transportation, or culturally competent care keeps people from screening. New programs are trying to fix that.

What’s Next?

Research is moving fast. AI is now helping analyze Pap smears. Paige.AI’s system got FDA approval in 2023. It can spot abnormalities faster and more consistently than humans in some cases.

Some studies suggest that after two negative HPV tests, you might be safe for six years instead of five. That’s still being studied, but it could mean fewer visits and less anxiety.

The future is clear: vaccination for kids, simple screening for adults, and tools that reach everyone-not just those who can easily get to a clinic.

What You Can Do Right Now

- If you’re under 26: Get the HPV vaccine if you haven’t already.

- If you’re 25-65: Ask your provider about HPV testing. Don’t wait for a Pap smear unless you’re in your 20s.

- If you’ve avoided screening: Ask about self-collection. It’s quiet, private, and effective.

- If you’ve had the vaccine: Still get screened. It’s not a substitute.

Cervical cancer used to be a leading cause of death for women. Today, it’s one of the most preventable. We have the tools. We just need to use them.

Can you get HPV even if you’ve been vaccinated?

Yes. The HPV vaccine protects against the most common cancer-causing types-mainly 16 and 18-but not all 14 high-risk strains. That’s why screening is still necessary, even for vaccinated people. The vaccine reduces your risk dramatically, but it doesn’t eliminate it entirely.

Do you need a Pap smear if you’re over 30 and get HPV testing?

Not necessarily. Primary HPV testing every five years is now the preferred method for people aged 25-65. You only need a Pap smear if your HPV test is positive and you need triage. For most, the HPV test alone is enough.

Is HPV testing painful?

Clinician-collected HPV tests are done the same way as a Pap smear-using a speculum and a small brush. It might feel uncomfortable, but it’s not usually painful. Self-collected tests are even easier-you do it yourself at home with a swab. No speculum, no appointment needed.

Can men be tested for HPV?

There’s no routine HPV test for men. The virus often clears on its own, and there’s no approved screening method for anal, throat, or penile HPV in the general population. But men can still benefit from vaccination, which prevents genital warts and some cancers. They also help reduce transmission by being vaccinated.

If I’ve had a hysterectomy, do I still need screening?

If you had a total hysterectomy for non-cancer reasons and your cervix was removed, you generally don’t need screening anymore. But if your cervix was kept (partial hysterectomy), you still need regular HPV testing. Always check with your doctor based on your medical history.

How often should I get screened if I’m HPV-positive?

If you test positive for HPV but your Pap test is normal, you’ll usually be retested in one year. If you’re still positive after a year, you’ll likely be referred for a colposcopy. If both tests are normal after two years, you can return to routine five-year screening. The goal is to monitor-not panic.

satya pradeep

November 17, 2025 AT 22:51Man, I got the HPV shot back in 2018 and thought I was immune to everything. Turns out, I still needed screening. Learned the hard way after a weird Pap result. Glad they pushed HPV testing over Pap smears now-way more accurate. Self-collection? I’m ordering one next month. No more awkward gyno appointments for me.

Kathryn Ware

November 19, 2025 AT 07:46This is one of the most important public health wins of the last decade and nobody talks about it enough. The drop in precancerous lesions in Australia? That’s not luck-that’s policy, science, and consistency. We’re talking about preventing a slow, painful death for thousands of women. And yet, in some parts of the U.S., people still think the vaccine causes infertility or is ‘too much too soon.’ 😔 The data doesn’t lie. Vaccinate early. Screen regularly. Self-collection is a game-changer for people who can’t access clinics. Let’s stop treating this like a political issue and start treating it like the medical emergency it was.

Also, if you’re over 26 and haven’t gotten the shot? Do it anyway. It’s not a waste. Your body still benefits from protection against strains you haven’t encountered. 💪

Leslie Douglas-Churchwell

November 21, 2025 AT 00:12Let’s be real-this whole HPV narrative is just Big Pharma’s latest money grab. 🤡 They push vaccines like they’re candy, then sell you $800 tests every 5 years. And don’t get me started on ‘self-collection.’ Who’s really behind those kits? The same labs that profit off false positives. I’ve read studies where 70% of HPV+ results resolve on their own-but they still scare people into colposcopies. The real cancer risk? Overmedicalization. 🚩

My mom had a hysterectomy in ’99 and they still sent her screening letters. That’s not medicine. That’s bureaucracy with a stethoscope.

kora ortiz

November 21, 2025 AT 11:58Elia DOnald Maluleke

November 23, 2025 AT 01:45One cannot help but reflect upon the profound metaphysical paradox inherent in this discourse: that humanity, having unlocked the molecular architecture of a virus capable of inducing malignancy, now stands at the precipice of its own eradication-yet remains shackled by the chains of apathy, misinformation, and institutional inertia. The HPV vaccine is not merely a biological intervention; it is an ethical imperative, a covenant between the present and the unborn. To neglect it is to consign future generations to the silent suffering of a preventable agony. And yet, in the shadow of algorithmic distraction and commodified healthcare, we choose distraction over duty. Is this not the tragedy of our age?

shubham seth

November 23, 2025 AT 01:52Y’all acting like this is some revolutionary breakthrough. Nah. This is just medicine finally catching up to the fact that people have vaginas and assholes and throats-and viruses don’t care about your gender, religion, or TikTok trends. HPV’s been around since cavemen were scratching their dicks with rocks. The only thing new here is that we finally stopped pretending it’s ‘dirty’ or ‘shameful’ to talk about. Good. Now let’s stop making it a privilege. If a woman in rural Kenya can swab herself with a $2 kit and avoid cancer, why the hell is this still a ‘debate’ in Texas? Stop being cute. Get tested. Get vaccinated. Stop acting like your cervix is a sacred temple that needs a priest to touch it.

Prem Hungry

November 24, 2025 AT 08:04As someone who works in rural health outreach in India, I can tell you-this article is spot on. We’ve rolled out self-collection kits in three states. Women who hadn’t seen a doctor in 12 years are now sending in swabs. One lady told me, ‘I thought I’d die before anyone asked me about this.’ That broke me. The vaccine? We’re getting 70% coverage in urban schools. Rural? Still struggling. But the shift is real. People are talking. No more whispers. No more shame. And yes, even men are asking for the shot now. Not because they’re scared of cancer-though they should be-but because their daughters are getting it, and they don’t want to be the reason their kids get sick. That’s the real win.

Bill Machi

November 25, 2025 AT 06:02Let’s cut through the propaganda. HPV is a normal virus. Most people get it. Most clear it. The vaccine? Fine. But turning this into a moral crusade is ridiculous. You’re not a bad person if you didn’t get it. You’re not a monster if you skipped screening. The real problem? The medical industrial complex turning a common infection into a lifetime of anxiety and bills. I had a positive HPV test. My doctor said ‘monitor.’ I waited a year. It was gone. No surgery. No trauma. Just biology doing its job. Why are we medicating normalcy?

Tarryne Rolle

November 26, 2025 AT 18:47Interesting how this article assumes everyone has access to ‘healthcare systems’ and ‘doctors.’ What about the millions of undocumented people in the U.S.? Or those without insurance? Or the trans men who still have cervixes but are terrified to walk into a gynecologist’s office? This isn’t prevention-it’s privilege. The real innovation isn’t the test. It’s the fact that we still haven’t made healthcare a human right. Until then, this is just a glossy brochure for people who can afford to care.

Jeremy Hernandez

November 28, 2025 AT 03:09Yeah sure, vaccinate the kids. But who’s paying for the follow-up? Who’s paying for the colposcopies? Who’s paying for the lost wages when you take a day off to get screened? This whole thing is a scam designed to keep people coming back for more. And don’t even get me started on AI analyzing Pap smears-next thing you know, your doctor’s replaced by an algorithm that misreads a cell and sends you into a panic. I’ve seen it happen. People get scared, get biopsied, get scarred. All for a virus that probably would’ve cleared on its own. We’re not saving lives-we’re creating a cancer industry.