When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just have a patent. It has patent exclusivity and market exclusivity-two different shields that keep generics off shelves. Most people think if a drug is patented, no one else can copy it. That’s not the whole story. The real gatekeeper? Sometimes, it’s not the patent. It’s the FDA.

Patent Exclusivity: The Legal Right to Exclude

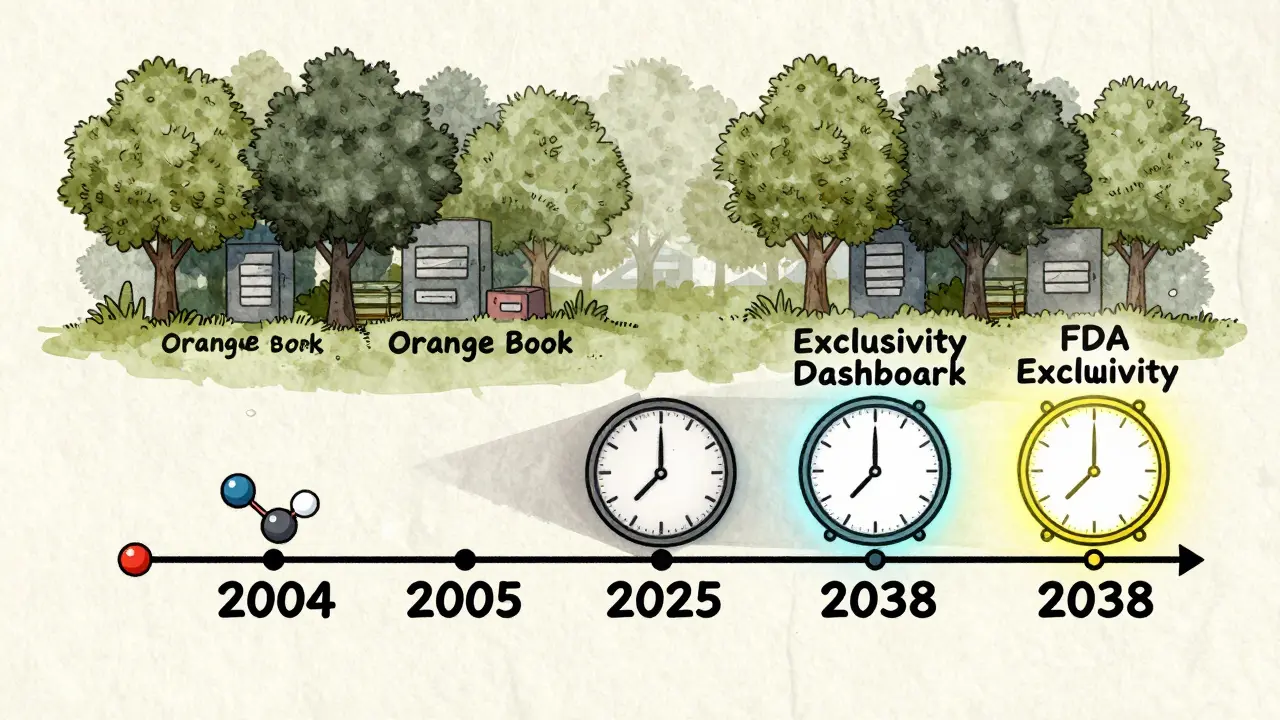

Patent exclusivity comes from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). It gives the drugmaker the legal right to stop anyone else from making, selling, or using their invention for 20 years from the day they filed the patent. Sounds simple, right? But here’s the catch: patents are filed years before a drug even gets approved by the FDA.

Drug development takes 10 to 15 years on average. That means by the time a drug reaches patients, half the patent clock might already be gone. A drug approved in 2025 could have only 5 to 7 years of patent life left. That’s not enough to recoup the $2.3 billion it cost to develop.

That’s why companies get extensions. Patent Term Extension (PTE) can add up to five years to the patent life, but only if the delay was caused by FDA review. And even then, the total market exclusivity can’t go beyond 14 years after FDA approval. So if a drug gets approved in 2024, the absolute latest it can be protected is 2038-even if the original patent was filed in 2004.

Patents also aren’t all equal. The strongest is a composition of matter patent-it protects the actual chemical structure. But many companies file secondary patents: methods of use, packaging, dosing schedules, or formulations. These are easier to get, harder to challenge, and often listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. In fact, 68% of patents listed there are secondary, not core.

Market Exclusivity: The FDA’s Secret Weapon

Market exclusivity is the FDA’s tool. It doesn’t care if the drug is patented. It doesn’t care if the molecule is 200 years old. If a company submits new clinical data to prove safety and effectiveness, the FDA blocks competitors from using that data-or even approving a copy-for a set time.

This is where things get wild. Take colchicine. It’s been used since ancient Egypt for gout. No one owned a patent on it. But in 2010, Mutual Pharmaceutical got FDA approval for a new formulation and submitted new clinical trials. Result? 10 years of market exclusivity. The price jumped from 10 cents a tablet to nearly $5. No patent. Just exclusivity.

The FDA grants several types of market exclusivity:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE): 5 years. During this time, the FDA won’t even accept a generic application.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating rare diseases (under 200,000 U.S. patients). Even if the drug isn’t patented, no one else can get approved.

- Pediatric Exclusivity: 6 months added to any existing patent or exclusivity period. Companies do this by running extra studies on kids. Since 1997, this has generated $15 billion in extra revenue.

- Biologics Exclusivity: 12 years under the BPCIA of 2009. This protects complex protein-based drugs like Humira or Enbrel.

- 180-Day Exclusivity: The first generic company to challenge a patent gets this. It’s worth $100 million to $500 million in extra sales.

Market exclusivity doesn’t need novelty. It doesn’t need innovation. It just needs new data. And the FDA enforces it automatically. No lawsuits. No lawyers. Just a checkbox on an application.

Why Both Exist: The Double Lock System

Patents and market exclusivity don’t replace each other. They stack. Think of them like two locks on a door. One is a physical lock (patent). The other is a keycard system (exclusivity). You need both to keep people out.

Here’s how it breaks down, based on FDA data from 2021:

- 27.8% of drugs have both patent and exclusivity

- 38.4% have only patent protection

- 5.2% have only exclusivity

- 28.6% have neither

That 5.2%? Those are the drugs without patents but still protected. Colchicine is one. So is the cholesterol drug Repatha. It had no composition-of-matter patent, but got 12 years of exclusivity because it was a new biologic.

And here’s the kicker: if a patent expires but exclusivity is still active, generics still can’t enter. Teva Pharmaceuticals found this out the hard way with Trintellix. The patent expired in 2021, but 3 years of exclusivity remained. They couldn’t launch until 2024. That cost them $320 million in lost sales.

Who Benefits? Who Pays?

Big pharma wins. Patients lose. Or at least, they pay more.

On average, branded drugs earn 65% of their total lifetime revenue in the first year after launch-right when both patent and exclusivity are active. That’s why companies fight to extend both. The Biotechnology Innovation Organization found that 73% of small biotech firms rely more on market exclusivity than patents for their main products. Why? Because patents are expensive to get, easy to challenge, and often invalid. Exclusivity? Harder to overturn.

And it’s getting worse. In 2022, 58% of new drugs had no composition-of-matter patent at all. Yet they still got exclusivity. That means the FDA is granting 10+ years of monopoly power to drugs that aren’t even new inventions. This is what experts call “evergreening”-keeping old drugs off the market by tweaking them just enough to qualify.

The cost? The U.S. spends $1.42 trillion on pharmaceuticals every year. Branded drugs make up 68% of that spending, even though they’re only 12% of prescriptions. That’s because generics can’t get in.

What’s Changing? The New Rules

The system is under pressure. In 2023, the FDA launched its Exclusivity Dashboard, a public tool that shows exactly when each drug’s exclusivity expires. Generic companies are now watching it like hawkers at a stock market.

Also in 2023, the PREVAIL Act proposed cutting biologics exclusivity from 12 to 10 years. The FDA also started requiring more detailed justifications for exclusivity claims-starting January 1, 2024. That means companies can’t just slap on a 5-year exclusivity label without proving they did real, independent studies.

And then there’s the global angle. The WTO waived patent rights for COVID vaccines. Now, people are asking: why not for cancer drugs? If that happens, market exclusivity could become the last line of defense for drugmakers.

Meanwhile, small companies are still getting burned. A 2022 survey found 43% of biotech firms thought patent = market protection. They didn’t file for exclusivity. Lost time. Lost money. Average cost? $1.7 million per mistake.

What Should You Know?

If you’re a patient: understand that high drug prices aren’t just about patents. They’re about regulatory loopholes.

If you’re in pharma: don’t assume a patent is enough. File for exclusivity. Miss it, and you lose years of revenue. The FDA doesn’t remind you. You have to ask.

If you’re a generic maker: study the Orange Book and the Exclusivity Dashboard. Look for drugs with expired patents but active exclusivity. That’s your target. And if you’re first to challenge a patent? You could get 180 days of exclusive sales-enough to fund your next 10 projects.

The bottom line? Patent exclusivity is about invention. Market exclusivity is about data. One is legal. The other is bureaucratic. But together? They’re the real reason your prescription costs what it does.

Robert Way

January 15, 2026 AT 08:13so like… patent is like a copyright for chemicals? and then the fda just says nope, even if you didnt invent it, you cant make it for 10 years? that makes zero sense. why am i paying $5 for colchicine? its from ancient egypt lmao

TooAfraid ToSay

January 17, 2026 AT 02:41oh wow another ‘big pharma bad’ post. next you’ll tell me water is expensive because corporations own rivers. wake up. if you dont like drug prices, move to india. or better yet-stop being a lazy entitlement monster and get a job that pays more than minimum wage. also colchicine? its not a miracle drug. its a poison if you overdose. chill.

Dylan Livingston

January 18, 2026 AT 22:41How utterly predictable. Another ‘educational’ post that pretends to be about transparency while quietly endorsing the very system that turns human suffering into quarterly earnings reports. Let me guess-you think the FDA is some neutral arbiter? Darling, the FDA is the gatekeeper of capitalist medicine. They don’t ‘grant’ exclusivity-they rubber-stamp corporate theft disguised as innovation. And let’s not pretend the 180-day exclusivity loophole for generics isn’t just a corporate poker game where the house always wins. The fact that we’ve normalized paying $10,000 a month for a pill that’s been around since the 1970s isn’t a market failure-it’s a moral collapse. And you? You’re just the polite audience clapping while the patient cries in the waiting room.

shiv singh

January 19, 2026 AT 02:10bro this is why america is broke. patents last 20 years but by the time drug is approved its already half gone? so they get extra years? why not just fix the approval process instead of letting pharma rip us off for 14 more years? i saw a guy in delhi buy the same drug for 20 cents. we are being played. and the fda is the accomplice. no wonder people are dying for meds.

Vicky Zhang

January 19, 2026 AT 21:31Okay, I know this sounds heavy, but I just want to say-this is so important. So many of us don’t realize that the reason our insulin costs $300 isn’t because it’s ‘hard to make’-it’s because the system is rigged to keep generics out. And those 6-month pediatric exclusivity extensions? That’s not helping kids-that’s just pharma gaming the system. I’m so glad someone broke this down. We need more people to understand this. You’re not just explaining science-you’re defending people’s lives.

Allison Deming

January 20, 2026 AT 16:26While the post presents a compelling narrative regarding the distinction between patent and market exclusivity, it is critically incomplete in its failure to address the role of regulatory capture and the revolving door between the FDA and pharmaceutical lobbying entities. The 12-year biologics exclusivity period, for instance, was not established on the basis of scientific merit but through legislative compromise influenced by industry contributions. Moreover, the assertion that market exclusivity requires ‘new data’ is misleading-much of this data is derived from redundant trials with statistically insignificant clinical endpoints, effectively creating a regulatory fiction that masks rent-seeking behavior. A rigorous policy analysis must confront these structural incentives, not merely describe them.

Sarah -Jane Vincent

January 20, 2026 AT 19:15you think this is bad? wait till you find out the fda secretly lets pharma companies pay for their own safety reviews. yeah. you read that right. the same company that made the drug pays the FDA’s contractors to approve it. and the orange book? it’s a lie. they list patents that don’t even cover the drug. i’ve seen the emails. this isn’t regulation. it’s a cartel. and the government is the enforcer. you think your prescription is expensive now? just wait until they start patenting your DNA.

Henry Sy

January 20, 2026 AT 23:34so let me get this straight-some guy in a lab tweaks a molecule so it’s ‘slightly different’ and now you gotta pay $500 a pill for something that used to cost a buck? and we call that innovation? bro, if my car company did that-made a 2010 model, changed the cupholder, and called it a ‘new model’-i’d burn it. but drugs? oh no, that’s ‘science.’ yeah right. this whole system is just pharma’s version of a pyramid scheme. someone’s making billions while grandma skips her meds. and we’re supposed to be impressed?

Anna Hunger

January 21, 2026 AT 04:33While the article correctly identifies the distinction between patent and market exclusivity, it neglects to emphasize the procedural safeguards that exist within the FDA’s framework to ensure public safety. Market exclusivity is not an arbitrary privilege; it is a statutory incentive designed to encourage investment in clinical research that demonstrates therapeutic benefit beyond existing treatments. Without such protections, the development of novel biologics and orphan drugs would be economically unviable. The system, while imperfect, balances innovation with access. Reform should target inefficiencies-not eliminate foundational incentives that enable life-saving therapies to reach patients in the first place.

Jason Yan

January 22, 2026 AT 02:49It’s wild to think about how we’ve turned healing into a math problem. We don’t ask ‘how can we make this affordable?’-we ask ‘how long can we charge the most?’ Patents were meant to reward innovation, not to lock away medicine like a treasure chest. But here we are, treating a child’s asthma inhaler like a luxury watch. I wonder-if we had a system where drug development was publicly funded, and profits were capped at a reasonable return, would we still have these insane prices? Maybe we’re not broken because of greed-we’re broken because we stopped imagining a different way.

Alvin Bregman

January 22, 2026 AT 14:13so like the fda just says no generics for 10 years even if the drug is 200 years old? that feels wrong. why dont we just make it free? i mean if its not a new invention why are we paying so much? also i think we should make all meds like ibuprofen-everyone can make it. why is this so hard to understand

Sarah Triphahn

January 22, 2026 AT 15:37the real scam? the people who wrote this think they’re exposing something new. newsflash-this has been public knowledge since 2010. the FDA publishes the exclusivity data. generic companies have been exploiting it for years. the only people fooled are the ones who still believe ‘innovation’ justifies $1000 pills. this isn’t a revelation. it’s a Yelp review of a corrupt system. and you’re still surprised? get a clue.

Susie Deer

January 24, 2026 AT 10:10americans think they deserve cheap drugs because they dont pay taxes? we fund this research. we pay for the labs. we pay for the trials. if you want cheap meds go to china. they dont care about innovation. we do. stop whining. the patent system works. if you cant afford your meds then get a better job. its not the drugs fault you make 15k a year