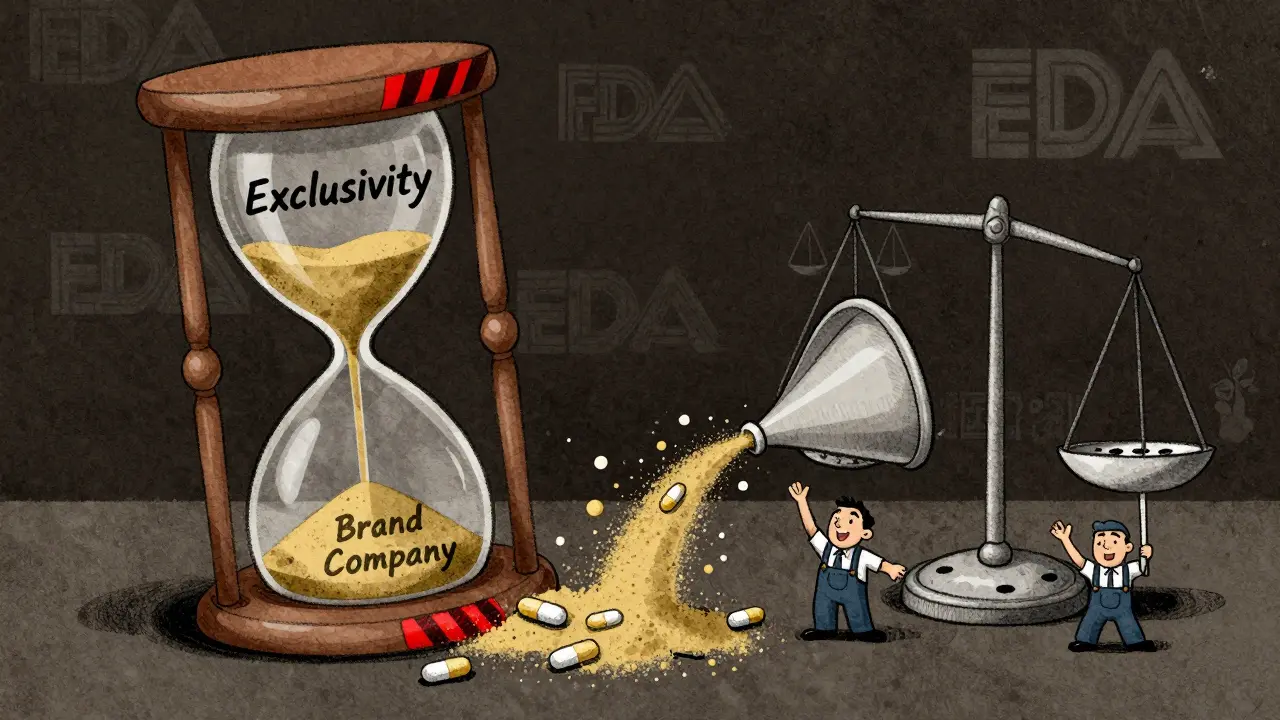

When a generic drug company challenges a brand-name drug’s patent and wins, it gets a powerful reward: 180-day exclusivity. For six months, no other generic can enter the market. That’s a golden window to capture most of the sales, often worth hundreds of millions of dollars. But here’s the catch: the brand-name company can still launch its own version of the drug-same active ingredient, same factory, same packaging, just without the brand name. That’s an authorized generic. And it’s legal. And it’s devastating to the first generic company’s profits.

How the 180-Day Exclusivity Rule Was Supposed to Work

The 180-day exclusivity rule was created in 1984 under the Hatch-Waxman Act. Its goal was simple: encourage generic drug makers to take on the risk and cost of challenging expensive brand-name patents. If a generic company filed a Paragraph IV certification-saying the brand’s patent was invalid or not infringed-and won in court or settled, they got the exclusive right to sell the generic version for six months. During that time, the FDA couldn’t approve any other generic versions of the same drug.This wasn’t just a reward. It was an incentive. Patent challenges cost between $2 million and $5 million in legal fees alone. For small generic companies, that’s a huge gamble. The promise of six months without competition was meant to make that gamble worth it. And it worked-for a while. Between 1984 and 2010, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system over $2 trillion. That’s because the first generic entrant could undercut the brand-name price by 80-90% and capture nearly all the market.

What Is an Authorized Generic? (And Why It Breaks the System)

An authorized generic isn’t a copy. It’s the exact same drug made by the brand-name company, just sold under a different label. No new approval needed. No bioequivalence studies. No waiting. The brand-name manufacturer simply takes the pills off the branded shelf and puts them in plain packaging. Then they sell them to pharmacies at the same low price the generic company is offering.Here’s why that’s a problem: the first generic company didn’t get to enjoy its exclusivity. The brand company, using its own distribution network and relationships with pharmacies, floods the market with its version. The result? Instead of capturing 80% of the market, the first generic company ends up with just 50%. Revenue drops by 30-50%. In some cases, like Teva’s fight over Humalog, the loss was $287 million.

According to FDA data, between 2005 and 2015, brand-name companies launched authorized generics in about 60% of cases where 180-day exclusivity was granted. That’s not a coincidence. It’s a strategy. And it’s perfectly legal under current law.

Legal Gray Zones and Court Battles

The law doesn’t say brand-name companies can’t launch authorized generics during the exclusivity period. It doesn’t mention them at all. That’s the loophole. The Hatch-Waxman Act was written before authorized generics became common. The lawmakers assumed that if a generic company won, it would be the only one selling the drug. They didn’t plan for the brand to come in and compete with its own product.Generic companies have tried to fight back in court. Some have argued that authorized generics violate antitrust laws by colluding with the first generic applicant to delay competition. But courts have consistently ruled that since the authorized generic is made by the brand company and not a third party, it’s not a collusion scheme. It’s just business.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has filed 15 antitrust lawsuits since 2010 against brand-name companies for allegedly using authorized generics to block competition. But they’ve had limited success. The FTC’s 2022 report admitted that the law itself is the barrier-not the behavior. Without a change in the statute, there’s little they can do.

How Generic Companies Are Adapting

Generic drug makers aren’t sitting still. They’ve learned to play the game differently. Today, 78% of first generic applicants negotiate deals with brand-name companies as part of patent settlement agreements. These deals often include promises: “We won’t launch an authorized generic if you drop your lawsuit” or “We’ll delay our authorized generic for 30 days after your launch.”These deals are risky. The FTC and the Department of Justice have cracked down on “pay-for-delay” agreements where brand companies pay generics to stay out of the market. But authorized generic delays are still allowed-as long as they’re not direct cash payments. It’s a legal tightrope.

Smaller generic companies are especially vulnerable. They don’t have the legal teams or financial reserves to fight long patent battles. Many now avoid Paragraph IV challenges altogether. One generic executive told a Reddit forum in early 2023: “If I know the brand will just slap their own version on the shelf, why risk $4 million and two years of my life?”

The Financial Impact: Numbers Don’t Lie

The numbers tell a clear story:- A first generic company without authorized generic competition can capture 80% of the market.

- With an authorized generic, that drops to 50%.

- Revenue loss averages 30-50%.

- Between 2015 and 2020, first generics captured only 52% of their theoretical revenue due to authorized generics.

- Companies now spend $500,000 to $1 million on consultants just to manage exclusivity timing and avoid losing days due to paperwork errors.

The FDA reports that 28% of first generic applicants between 2018 and 2022 lost part of their exclusivity because they misfiled paperwork, missed the commercial marketing trigger, or shipped product too early. That’s not just bad luck-it’s systemic pressure. The clock starts the moment the drug is shipped to customers. Miss the timing by a day, and you lose a day of exclusivity. No warning. No grace period.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

At first glance, consumers win. Authorized generics mean more competition. Prices drop faster. A 2021 RAND Corporation study found that when an authorized generic enters alongside the first generic, prices fall 15-25% more than when only one generic is on the market.But the bigger picture is more complicated. The whole point of the 180-day exclusivity rule was to create a financial incentive for generic companies to challenge patents. Without that incentive, fewer companies will take the risk. Fewer challenges mean fewer generics overall. That means higher prices down the road.

Brand-name companies win in the short term. They keep market share and avoid the full price drop. But in the long term, they lose public trust. And they risk future legislation that could shut down the authorized generic loophole entirely.

What’s Changing? The Push for Reform

There’s growing pressure to fix this. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act has been reintroduced in Congress multiple times since 2009. The latest version, S. 1665/H.R. 3928, would ban brand-name companies from launching authorized generics during the 180-day exclusivity period.FDA Commissioner Robert Califf testified in March 2023 that the agency supports this change. The FTC agrees. Their 2022 report said that banning authorized generics during exclusivity would boost first-generic revenues by 35% on average. That could lead to 20-25% more patent challenges-meaning more generics sooner.

But the pharmaceutical industry, through groups like PhRMA, pushes back. They say authorized generics help patients get cheaper drugs faster. And they’re not wrong. But the question is: should the first generic company be punished for doing exactly what the law asked them to do?

What This Means for Patients and Pharmacists

For patients, the system still delivers lower prices. But the path to those prices is broken. Instead of a clean transition from brand to generic, we get a messy overlap. Pharmacists see it every day: a patient switches from a branded drug to a generic, only to get a different generic a week later-same pill, different label.Pharmacists can’t always tell the difference. The FDA doesn’t require authorized generics to be labeled as such. So patients might think they’re getting a cheaper generic, when they’re actually getting the brand’s own version. It’s confusing. And it undermines trust in the generic system.

The real cost isn’t just in dollars. It’s in confidence. If generic companies stop filing patent challenges because the reward is gone, the pipeline dries up. That means fewer generics on the market five years from now. And that means higher drug prices for everyone.

Final Thoughts: A System in Need of Repair

The 180-day exclusivity rule was a brilliant idea. It worked. But the authorized generic loophole turned it into a trap. The law didn’t anticipate that the brand would become its own competitor. Now, the system is rigged against the very companies it was meant to empower.Until Congress acts, the game will stay the same: big pharma wins. Small generics lose. Patients get lower prices-but only because the system is leaking money from the wrong place.

The fix is simple: ban authorized generics during the 180-day window. It’s not about protecting profits. It’s about keeping the incentive alive. Without it, the next generation of generic drugs won’t come.

Rosalee Vanness

January 14, 2026 AT 04:04Okay, so let me just say this-I’ve been in pharma compliance for 17 years, and this whole authorized generic loophole is like watching someone build a house out of Jenga blocks and then pull the bottom one out while yelling ‘SURPRISE!’ The system was designed to reward courage, not punish it. Generic companies aren’t some shady back-alley drug dealers-they’re the underdogs who bet their entire company on a legal Hail Mary. And then the big boys just... slide their own version in under the same label? No fines. No penalties. Just a shrug and a ‘it’s legal.’ It’s not capitalism. It’s corporate theater with a side of moral bankruptcy.

I’ve seen startups fold because they spent $4 million on a patent challenge, only to have the brand drop an authorized generic the same day. The FDA doesn’t even require labeling to distinguish them. Patients think they’re saving money, but they’re being sold the exact same pill, just with a cheaper box. And the worst part? Nobody’s talking about how this kills innovation. Why would a small firm risk everything if the reward gets gutted before they even get to cash in?

It’s not just about money-it’s about trust. When pharmacists can’t tell the difference between a real generic and the brand’s knockoff, how are patients supposed to believe in generics at all? I’ve had patients come in crying because their insurance switched them to ‘generic’ and then switched again because the ‘new generic’ didn’t work the same. Spoiler: it was the same damn pill. Just repackaged.

And don’t get me started on the paperwork traps. Miss a filing by a day? Lose a day of exclusivity. No grace period. No warning. It’s like being told you won the lottery, but then they say, ‘Oops, your ticket had a smudge. Sorry.’

The fix? Simple. Ban authorized generics during exclusivity. Not complicated. Not radical. Just… fair. The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t create this mess. The industry did. And now we’re all paying the price-in higher prices, fewer generics, and a system that rewards greed over guts.

mike swinchoski

January 15, 2026 AT 08:39This is why we can’t have nice things. Generic companies are just greedy and want a monopoly. If the brand wants to sell their own version, that’s their right. Stop crying about it.

Angel Tiestos lopez

January 15, 2026 AT 14:10bro. imagine being the underdog who fights the dragon… only for the dragon to turn around and sell the same sword you used to beat it… for less money 😭🪓💊

it’s like training your whole life to win a race… then the guy who made the track just shows up in your shoes and runs faster 🤡

the system ain’t broken-it’s rigged. and the worst part? we’re all just stuck watching the show while the players get richer. #hatchwaxmanfail

Acacia Hendrix

January 17, 2026 AT 03:58From a regulatory economics standpoint, the authorized generic mechanism represents a classic case of regulatory capture-where the statutory framework fails to account for emergent strategic behavior by incumbents. The absence of explicit prohibition in the Hatch-Waxman Act creates a negative externality wherein the incentive structure for Paragraph IV filers is systematically undermined by vertically integrated brand manufacturers. This constitutes a market failure in the generic entry ecosystem, as the expected rent capture asymmetry (80% vs. 50%) distorts risk-reward calculus, leading to suboptimal patent challenge volume.

Moreover, the FDA’s non-disclosure requirement regarding authorized generic labeling exacerbates informational asymmetry in the supply chain, violating the principle of consumer transparency in pharmaceutical procurement. The resulting erosion of trust in generic substitution protocols has measurable downstream effects on adherence and formulary adoption.

Until statutory intervention occurs-specifically, codifying exclusivity protection against manufacturer self-competition-the current equilibrium will persist as a Pareto-inferior state. The FTC’s 2022 findings are empirically sound: a 35% revenue uplift for first filers correlates directly with increased challenge frequency, which in turn drives down aggregate drug expenditures. The solution is not ideological-it’s actuarial.

Adam Rivera

January 18, 2026 AT 12:24Man, I’ve worked in pharmacy for 20 years, and this whole thing just makes me sad. I’ve seen patients switch from brand to generic and then get confused when the pill looks different a week later. They think something’s wrong with the medicine. But it’s the same exact thing. Just a different label. And the worst part? They don’t even know they’re getting the brand’s version.

I get why the big companies do it. But man… it just feels dirty. Like they’re cheating the whole system. The generics are the ones taking the risk, spending millions, fighting in court. And then the brand just pops in with the same pill and steals half the market. It’s not fair.

And yeah, prices drop faster-but at what cost? If no one’s willing to challenge patents anymore because it’s not worth it, we’re gonna see fewer generics down the road. And that’s gonna hurt everyone in the end.

Priyanka Kumari

January 20, 2026 AT 09:31As someone from India where generics are the backbone of healthcare access, I find this entire situation deeply troubling. The 180-day exclusivity rule was meant to empower small players to challenge monopolies-not to let big pharma sabotage them with their own clones. This isn’t just an American issue; it’s a global one.

When generics fail to thrive because of loopholes like authorized generics, it weakens the entire supply chain. Countries like mine rely on affordable generics to treat diabetes, HIV, and hypertension. If the incentive to innovate in patent challenges disappears, fewer drugs will be brought to market globally.

It’s heartbreaking to see a system designed to help the poor being twisted to protect corporate profits. The fix isn’t complicated: ban authorized generics during exclusivity. Let the first filer breathe. Let them earn what they fought for. Otherwise, we’re all just delaying the inevitable: higher prices for everyone.

Avneet Singh

January 21, 2026 AT 19:22Let’s be real-this is just generic companies whining because they didn’t get a free pass. The brand has every right to sell their own product under a different label. If you can’t handle competition, don’t enter the game. Also, ‘authorized generic’ isn’t even a real term-it’s just the original drug. Stop pretending it’s some evil scheme.

vishnu priyanka

January 22, 2026 AT 16:22so like… the brand makes the drug, right? then the generic says ‘hey i’m gonna sue you’ and wins. cool. then the brand just says ‘ok here’s my version, same pill, same factory, cheaper’ and boom-poof, the generic’s whole 6-month dream is now a 3-month footnote.

it’s like winning a race, then the guy who built the track shows up wearing your shoes and crosses the line first.

and the FDA doesn’t even make them label it? bro. that’s not transparency. that’s gaslighting.

also, why is nobody talking about how this makes pharmacists’ lives hell? i’ve had patients come in mad because their ‘generic’ changed again. it’s the same damn pill. but now they think it’s broken.

someone needs to fix this. before the next generation of generics just says ‘fuck it’ and never challenges another patent.

Alan Lin

January 24, 2026 AT 15:38Let me be clear: this is not a debate about pricing. This is about justice. The Hatch-Waxman Act was a covenant between Congress and the small generic manufacturers who were willing to risk everything to break monopolies. The authorized generic loophole is a breach of that covenant. The brand companies didn’t just exploit a gap-they weaponized it. And now, because of this, fewer companies are filing Paragraph IV certifications. The result? Fewer generics. Higher prices. More suffering.

The FDA and FTC have the data. They know this is wrong. But they’re waiting for Congress to act. And Congress is waiting for a crisis. Meanwhile, patients are being misled. Pharmacists are confused. And the companies that did the hard work are being erased from the marketplace.

This isn’t capitalism. It’s corporate theft dressed up as legal strategy. And if we don’t fix it now, we’ll wake up in five years wondering why no one’s challenging patents anymore-and why every drug costs $10,000 a year.

Scottie Baker

January 26, 2026 AT 10:13ugh. I’m so sick of this. I work in a clinic. I see people skipping doses because their meds got ‘switched’ again. They think the new generic is weaker. It’s not. It’s the same damn pill. But now they’re paranoid. And the brand doesn’t even label it? That’s not just shady-it’s dangerous.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘deals’ between big pharma and generics. ‘Oh, we’ll delay our authorized generic for 30 days if you drop your lawsuit.’ That’s not a deal. That’s coercion. And the FTC lets it slide because it’s not cash? Bullshit.

These companies are playing chess while the rest of us are stuck picking up the pieces. And the worst part? No one’s even talking about how this affects rural communities. If the generics stop coming, rural pharmacies can’t afford to stock them. Then what? Patients drive 2 hours for their insulin? No. We’re already losing this game.

Anny Kaettano

January 26, 2026 AT 21:10The authorized generic loophole is a structural failure in the incentive architecture of the U.S. pharmaceutical market. The regulatory framework assumes rational actors operating under symmetric information, yet the reality is a profound asymmetry: brand manufacturers retain full control over manufacturing, distribution, and labeling, while the first generic filer operates under a ticking clock with zero margin for error.

Moreover, the absence of mandatory disclosure requirements for authorized generics constitutes a violation of the principle of informed substitution-a cornerstone of generic drug policy. Patients are not merely consumers; they are stakeholders in therapeutic continuity. When a pill’s origin is obfuscated, trust in the entire generic ecosystem erodes.

The FTC’s 2022 analysis correctly identifies that a ban on authorized generics during exclusivity would increase first-filer revenue by 35%. This is not a theoretical gain-it’s a measurable catalyst for increased patent challenges, which in turn accelerates market entry of low-cost therapeutics. The cost of inaction is not fiscal-it’s human.

James Castner

January 28, 2026 AT 19:23This is a textbook example of how well-intentioned legislation can be hollowed out by unintended consequences. The Hatch-Waxman Act was a landmark achievement-designed to democratize access to life-saving medicines by empowering the underdog. But the emergence of the authorized generic as a strategic tool has turned that empowerment into a trap.

Let’s reframe the question: if a generic company invests $5 million to challenge a patent and wins, why should the brand be allowed to immediately undercut them with their own version? It’s not competition. It’s sabotage disguised as legality. The brand didn’t innovate. They didn’t take a risk. They simply waited for someone else to clear the path… then walked right in.

And the real tragedy? It’s working. Generic companies are opting out. Why risk everything when the reward is guaranteed to be stolen? The result is a shrinking pipeline of patent challenges. Fewer challenges mean fewer generics. Fewer generics mean higher prices. And patients? They’re the ones who pay-in dollars, in health, in dignity.

The fix is simple: amend the law to prohibit authorized generics during the 180-day exclusivity window. Not because we’re protecting profits. But because we’re protecting the principle that if you fight the battle, you get to reap the reward. That’s not radical. That’s just fair.

Milla Masliy

January 29, 2026 AT 20:26I’ve been a pharmacist for 15 years and I’ve seen patients cry because their ‘generic’ changed again. They think it’s not working. But it’s the same pill. Just repackaged. And no one tells them. Not the pharmacy. Not the insurance. Not the FDA.

It’s not just about money. It’s about trust. If people stop believing in generics, they’ll go back to paying $1,000 for a pill that’s the same as the $10 version. And that’s how we lose.

Someone needs to fix this. Before it’s too late.

Damario Brown

January 30, 2026 AT 07:24generic companies are just crybabies. if you can't handle competition, don't file. also, authorized generics are just the original drug. why is this even a thing? the system works fine. stop whining.

btw, the real problem is the FDA's paperwork traps. if you miss a filing by a day, you lose a day? that's not a loophole, that's incompetence. blame the generic companies for not having better lawyers.

also, i'm pretty sure this whole thing is just a distraction from the real issue: drug prices are high because the government won't negotiate. not because of authorized generics. #stopthehysteria

James Castner

January 30, 2026 AT 13:58Actually, Damario, your point about FDA paperwork is valid-but it’s a symptom, not the cause. The system is designed to be a minefield. Why? Because it’s meant to intimidate small players. The 180-day exclusivity window isn’t just about time-it’s about precision. One missed shipment? One misfiled form? You lose everything. That’s not incompetence. It’s intentional. The brand companies know this. And they use it.

So yes, the paperwork is a trap. But the authorized generic is the trapdoor beneath it. One’s a glitch. The other’s a strategy. And together? They’re a death sentence for small generic firms.