Every time you pick up a generic prescription, there’s a hidden system at work - one shaped by federal laws, corporate contracts, and state regulations. It’s not just about what the drug costs. It’s about how pharmacies get paid, and why sometimes, even a cheap generic can leave you paying more than you expect.

How Generic Drugs Got Their Price Tag

The modern system for paying for generic drugs started in 1984 with the Hatch-Waxman Act. Before that, generic drugs were rare. The law made it easier for companies to copy brand-name medicines without repeating expensive clinical trials. In return, brand-name companies got extra patent protection. It was a trade-off: more generics, faster, but with some guardrails. That law didn’t just change how drugs got approved. It set the stage for how they’d be paid for. Suddenly, pharmacies had to figure out how to reimburse for drugs that cost a fraction of the brand version. That’s where reimbursement models came in - and why today, your pharmacy might get paid differently depending on whether you’re on Medicare, Medicaid, or paying cash.Two Main Ways Pharmacies Get Paid for Generics

There are two big systems pharmacies use to get reimbursed for generic drugs: Average Wholesale Price (AWP) and Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC). AWP used to be the standard. It’s a list price set by manufacturers, often inflated, and pharmacies got paid a percentage off that. But since generics don’t have a true market price like branded drugs, AWP became unreliable. So most plans switched to MAC. MAC is simpler: the plan sets a fixed maximum amount they’ll pay for a specific generic drug - say, $3.50 for 30 tablets of lisinopril. If the pharmacy bought it for $2.80, they keep the $0.70. But if they paid $4.10 at the wholesaler? They eat the loss. That’s the risk. And it’s why some independent pharmacies are barely breaking even on generics. In 2023, the average profit margin on a generic prescription was just 1.4%. Five years earlier, it was over 3%. That drop isn’t due to cheaper drugs - it’s because reimbursement rates haven’t kept up.Medicare Part D and the Hidden Rules

Medicare Part D covers nearly 51 million people. And it’s where things get complicated. Each Part D plan has its own formulary - a list of covered drugs - and each drug is placed in a tier. Generics usually land in Tier 1, meaning the lowest copay. But here’s the catch: not all generics are treated the same. A plan might cover one brand of generic lisinopril but not another. If your pharmacy doesn’t stock the preferred version, you might pay more - even though both are the same active ingredient. Plans also use prior authorization for generics. That means your doctor has to jump through hoops to get a non-preferred generic approved. In 2022, 28% of Part D plans required prior authorization for at least one generic drug. That’s not about safety. It’s about steering patients toward drugs that give the plan the biggest rebate. And then there’s the donut hole - the coverage gap. Even though most generics are cheap, if you’re hitting your deductible or in the gap, you pay full price until you hit catastrophic coverage. That’s why some seniors end up skipping doses, even on $3 pills.

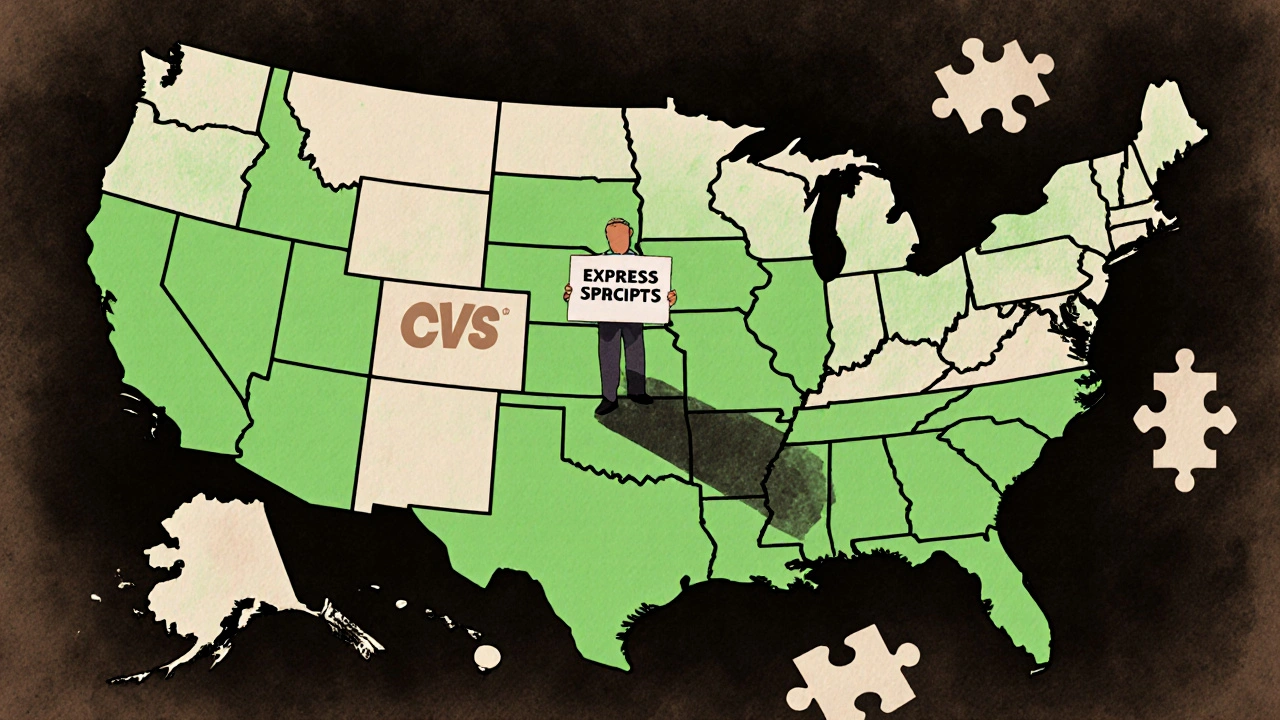

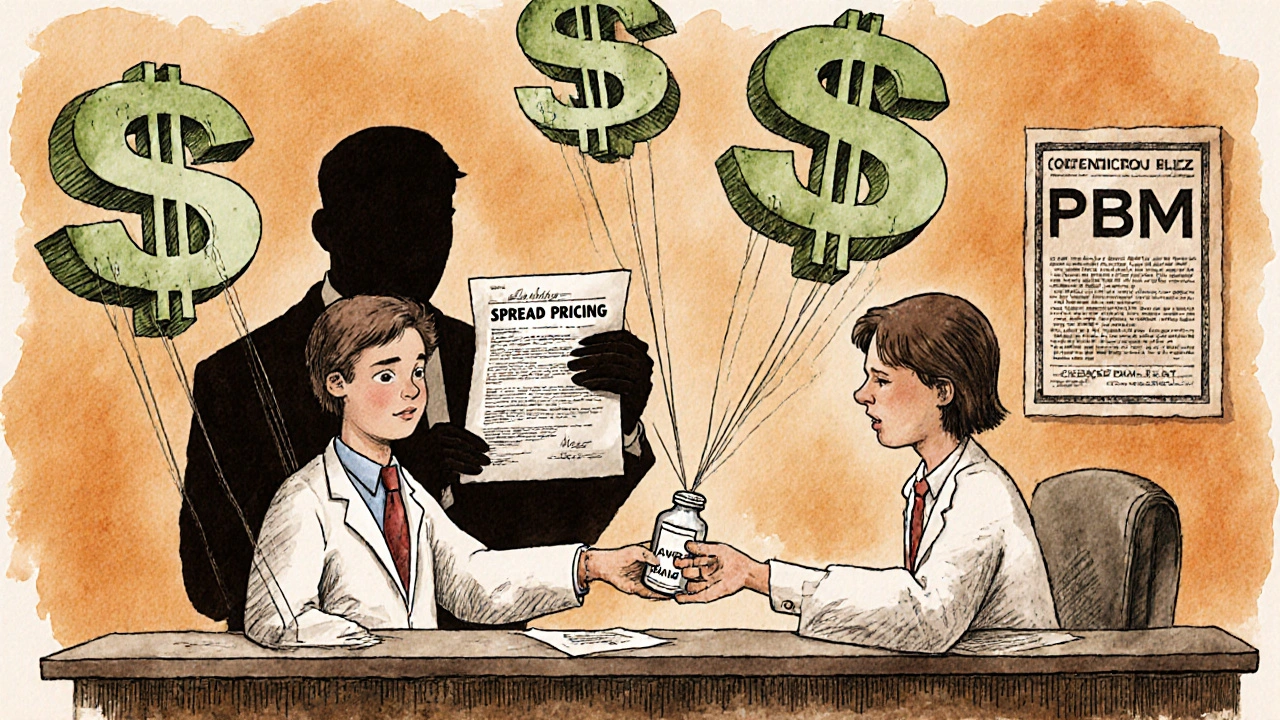

Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Middlemen

Behind every prescription claim is a Pharmacy Benefit Manager - or PBM. CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRX control over 80% of all prescription claims in the U.S. They don’t sell drugs. They don’t run pharmacies. They negotiate between drug makers, insurers, and pharmacies. PBMs make money in three ways: rebates from drug companies, the spread between what insurers pay and what pharmacies get paid, and by owning their own pharmacies. That last one is the big problem. If a PBM owns a pharmacy, they’ll steer patients there. And they’ll pay their own pharmacy more than they pay independent ones. That’s called steering. It’s legal. But it’s not fair. Independent pharmacies lose business. Patients lose choice. And everyone pays more in hidden fees. Worse, PBMs used to use “gag clauses” - contracts that stopped pharmacists from telling customers, “Hey, this $4 generic is cheaper if you pay cash.” Those were banned in 2018. But the damage is done. Many people still don’t know they can save money by skipping insurance for cheap generics.State Laws Are Changing the Game

Federal rules set the stage, but states are now stepping in. As of 2023, 44 states passed laws to regulate how PBMs reimburse pharmacies. Some require PBMs to pay at least the pharmacy’s actual cost for a generic. Others ban spread pricing entirely. A few even require PBMs to disclose their rebate deals. In New York, pharmacies now get paid the actual acquisition cost plus a dispensing fee - no more guessing games. In California, PBMs must tell patients if paying cash is cheaper. These laws aren’t perfect, but they’re pushing transparency. Medicaid programs use Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs) to control costs. If a drug isn’t on the list, the pharmacy won’t get paid. That means even if your doctor prescribes a generic, if it’s not on your state’s PDL, you’re stuck paying out of pocket - or switching to a different one.

The Drug List: What’s Coming Next

In 2025, CMS is testing a new model called the Medicare $2 Drug List. It’s simple: pick about 100 to 150 generic drugs that are clinically important, widely used, and cheap - and cap the patient’s copay at $2. Drugs like metformin, levothyroxine, and atorvastatin are likely candidates. The goal? Reduce confusion, improve adherence, and cut costs. If it works, it could become permanent. This model is based on what big retailers like Walmart and Costco already do. They offer $4 generics for 30 days. But Medicare’s version is designed to work within the Part D system - with plans required to include these drugs in their formularies and charge the same low copay. It’s not a magic fix. It doesn’t touch PBM rebates or manufacturer pricing. But it gives patients real savings and takes away one layer of complexity.Why This Matters to You

If you take generics, you’re part of this system. And you’re paying for it - whether you know it or not. You might be paying more than you should because:- Your plan doesn’t cover the generic your pharmacy stocks

- Your pharmacist can’t tell you the cash price is lower

- Your doctor had to fight to get a prior authorization approved

- You’re stuck in the Part D donut hole because your deductible is too high

Matthew Higgins

November 30, 2025 AT 17:57Man, I just paid $12 for lisinopril at my local pharmacy. Walked over to Walmart, same thing, $4 cash. No insurance needed. I don’t get how we’re still letting this system eat people alive.

It’s not rocket science. If the drug costs $1.20, why are we billing $8? The middlemen are laughing all the way to the bank while seniors skip doses.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘preferred generic’ crap. Same active ingredient. Different pill color. Different price. That’s not healthcare. That’s a casino.

stephen idiado

December 2, 2025 AT 13:43AWP is a fiction. MAC is a trap. PBMs are rent-seeking oligarchs. The $2 Drug List is a band-aid on a hemorrhage.

Real reform? Ban spread pricing. Ban vertical integration. Break up CVS Caremark and OptumRX. Otherwise, it’s just theater.

Peter Axelberg

December 3, 2025 AT 02:22I’ve been working in pharmacy for 18 years. I’ve seen this shift from AWP to MAC to now ‘retail pricing transparency’-and honestly? It’s been a slow-motion car crash.

Independent pharmacies used to be community hubs. Now? They’re barely hanging on. One bad batch of reimbursement delays and they’re out.

And don’t even get me started on how PBMs use formularies like a weapon. I had a patient last week who needed metformin. Her plan covered one brand. We stocked another. She had to pay $18 out of pocket. Same molecule. Same manufacturer. Just a different lot number.

It’s not just broken. It’s designed to fail the little guy.

Meanwhile, the big chains? They get preferential rebates, their own mail-order services, and the PBM’s own pharmacy network. It’s not capitalism. It’s a rigged game.

And yeah, I know the ‘cash is cheaper’ advice. But how many seniors know to ask? How many are too proud to admit they can’t afford the co-pay? I’ve seen people cry over a $3 pill.

Change isn’t coming from the top. It’s coming from us-patients, pharmacists, the ones who show up every day and say ‘this isn’t right.’

Jennifer Wang

December 3, 2025 AT 05:23While the structural issues outlined are accurate, it is imperative to distinguish between regulatory intent and operational outcomes. The Hatch-Waxman Act successfully increased generic market penetration from 19% to over 90%-a public health triumph.

The current reimbursement inefficiencies stem not from legislative failure, but from the absence of standardized, auditable acquisition cost reporting mechanisms across state and federal payers.

Furthermore, the prohibition of gag clauses, while commendable, remains inconsistently enforced. Compliance monitoring by state boards of pharmacy remains under-resourced.

Recommendation: Mandate real-time acquisition cost disclosure via the National Drug Code (NDC) database, synchronized with Medicaid and Medicare Part D formularies. This would enable true price transparency without requiring patient advocacy as a prerequisite for equitable access.

Bernie Terrien

December 3, 2025 AT 23:38PBMs are the vampire squid of healthcare. They don’t make drugs. They don’t dispense them. They just suck the blood out of pharmacies and patients while wearing a white coat and calling themselves ‘cost savers.’

They’re the reason your grandma’s $3 pill costs $15 on insurance. They’re the reason your pharmacist can’t tell you the truth. They’re the reason independent pharmacies are vanishing like dial-up modems.

And now they want us to cheer for a $2 list? That’s not reform. That’s them handing us a crumb so we stop screaming.

Tina Dinh

December 5, 2025 AT 18:47OMG I JUST REALIZED I’VE BEEN OVERPAYING FOR MY THYROID MEDS FOR YEARS 😭

Went to CVS, paid $12 with insurance. Walked next door to Target-$4 CASH. I cried. Like, full ugly cry.

Y’all. ASK FOR THE CASH PRICE. ALWAYS. Even if you have insurance. Even if you’re ‘supposed to’ use it.

PS: My pharmacist didn’t even tell me. I had to Google it. That’s messed up. 🙏

jamie sigler

December 7, 2025 AT 17:23So… what’s the point again? We all know the system’s broken. But nobody’s doing anything. So why are we even talking about this?

Andrew Keh

December 7, 2025 AT 17:26It’s frustrating, but I think we’re seeing the beginning of a shift. More people are asking about cash prices. More states are passing laws. The $2 list might be small, but it’s a signal.

Maybe the next step is patient education-like, actual public service campaigns. Not just ‘ask your pharmacist,’ but ‘here’s how to do it, and here’s why it matters.’

We don’t need to fix everything at once. Just start making the invisible visible.

Sullivan Lauer

December 7, 2025 AT 21:40I’ve watched this system collapse from the inside. I used to work for a PBM. Not as a exec. As a data analyst. I saw the spreadsheets. I saw the rebates. I saw how they’d move a drug from Tier 1 to Tier 3 just because a competitor offered a bigger kickback.

It’s not about health. It’s about profit.

And the worst part? The people who designed this? They think they’re heroes. They say they’re ‘managing costs.’ But they’re not managing anything. They’re gaming a system designed to help people.

I quit because I couldn’t sleep at night. I started volunteering at a free clinic. Now I help people navigate this mess. I tell them: ‘Your pharmacist isn’t lying. The system is.’

And if you’re reading this? Do one thing today. Go to your next pharmacy. Ask: ‘What’s the cash price?’

That’s your power. That’s how we change this.

One question. One $4 pill. One saved life at a time.

Geoff Heredia

December 9, 2025 AT 00:47Let’s be real. This isn’t about reimbursement. It’s about control.

Who owns the data? Who owns the pharmacies? Who owns the formularies?

CVS, Express Scripts, Optum-they’re all owned by the same shadowy conglomerates that also own insurance companies, hospitals, and now, AI health startups.

This is a coordinated effort to monopolize healthcare. The $2 list? A distraction. A PR move to make you think they’re helping.

They’re not. They’re just moving the chess pieces.

Next up: mandatory genetic testing before you can get a generic. Because why not?

Wake up. This is the new normal. And they’re not going to fix it. You have to break it.

Subhash Singh

December 10, 2025 AT 13:44It is a matter of considerable concern that the economic incentives embedded within the current pharmaceutical reimbursement architecture systematically disincentivize cost-efficient dispensing practices, particularly among community-based pharmacies operating under tight margins.

Furthermore, the absence of a unified, nationally standardized acquisition cost benchmark impedes equitable access and fosters regional disparities in pharmaceutical affordability.

It is therefore proposed that a federal mandate be enacted to require all Pharmacy Benefit Managers to publish, in real time, the actual acquisition cost of all generic medications, alongside the net reimbursement rate paid to pharmacies, for public auditability.

Such transparency would not only restore fiduciary integrity to the system but also empower patients with actionable, evidence-based information to make informed healthcare decisions.

Matthew Higgins

December 10, 2025 AT 15:11That’s the thing. I asked my pharmacist yesterday. He said, ‘I wish I could tell you more, but I’m not allowed to.’

Then he leaned in and whispered: ‘Go to GoodRx. Type in your drug. See the cash price. Then come back.’

He risked his job to tell me that.

That’s the real hero.